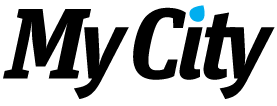

For the Miller family of New Lothrop, their son’s slowly worsening “lazy eye” was the only hint of a life-threatening condition. At seven years old, Braden Patrick Miller – affectionately called “Buddy” by his family – was playing basketball with his friends at school, when he fell and hit his head on the cement. What would have resulted in no more than a nasty bump on the head for a healthy child, instead, rendered Buddy hardly able to walk. Jeni Miller, his mother, recalls that day. “I had never been so scared, when the school called and said he was drooling, his eyes were dilated, he couldn’t stand up on his own and that he might need an ambulance. His dad (Brad) and I both showed up, and at first, I was relieved.” Buddy had bounced back a bit after the fall by the time they arrived and kept reassuring his very upset mother that he was fine. “We thought maybe he just had a mild concussion, but then, I asked him to walk over to his dad. His leg was dragging and there was a definite balance issue. He kept saying that he was okay, but I knew something was wrong.” Not wanting to alarm Buddy, and also afraid of what it could be, they took him home and made a few phone calls. “He kept saying his foot was just numb, and that he was okay,” she explains.

For the Miller family of New Lothrop, their son’s slowly worsening “lazy eye” was the only hint of a life-threatening condition. At seven years old, Braden Patrick Miller – affectionately called “Buddy” by his family – was playing basketball with his friends at school, when he fell and hit his head on the cement. What would have resulted in no more than a nasty bump on the head for a healthy child, instead, rendered Buddy hardly able to walk. Jeni Miller, his mother, recalls that day. “I had never been so scared, when the school called and said he was drooling, his eyes were dilated, he couldn’t stand up on his own and that he might need an ambulance. His dad (Brad) and I both showed up, and at first, I was relieved.” Buddy had bounced back a bit after the fall by the time they arrived and kept reassuring his very upset mother that he was fine. “We thought maybe he just had a mild concussion, but then, I asked him to walk over to his dad. His leg was dragging and there was a definite balance issue. He kept saying that he was okay, but I knew something was wrong.” Not wanting to alarm Buddy, and also afraid of what it could be, they took him home and made a few phone calls. “He kept saying his foot was just numb, and that he was okay,” she explains.

Jeni brought her son to Hurley Medical Center’s ER, where the physician’s assistant told them, based on the information she provided, that there was nearly no chance that Buddy had a concussion and he was about to be sent home. But, Jeni knew something was wrong with her son. “He was trying so hard to appear like he was fine, trying so hard to walk normally and just couldn’t,” she shares. Before they were given the all-clear, Jeni says a doctor (Dr. Webber) looked at Buddy and shook his head. “He had Buddy do a bunch of tests – had him hold his arms up and one would fall down; had him touch his nose – and everything was off. I will never forget the way the doctor’s face looked, like he knew this was not right. He ordered a CT scan immediately and shortly after, came back and said there was a mass in Buddy’s brain stem and they didn’t know what it was. But, they needed to get him to C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital immediately and there was an ambulance on its way to pick him up.” Just like that, the Miller family was rushed into a panic, having no idea what was going to happen, but knowing that something was terribly wrong. What would come next would be the hardest thing they would ever have to face.

“We were at C.S. Mott for the night and additional scans were ordered,” Jeni continues. “They called Brad and I into a room the next afternoon, and a team of three physicians told us, ‘your son has DIPG, Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma,’ and that it was cancer. Brad’s immediate response was, ‘how do we get rid of it, what can we do?’ They told us, ‘nothing, it’s inoperable. There is no cure for it. Our only option for you is 30 rounds of radiation with the hope of a 6-9-month ‘honeymoon period’ to go and make memories.’” After that, Jeni only remembers pieces of what happened, saying, “it was almost like I was in a movie, watching myself.” She ran from the room into the hospital hallway, screaming. “I just remember having to run away from it. When they brought me back, we were only able to ask a few questions and then were sent home. We had no idea what our next step would be,” she says.

With their son given only nine months to live and very few options, the one thing they did not do was give up. The Miller family’s close friends and relatives acted quickly, setting up a facebook page for Buddy and a GoFundMe crowdfunding account, they also became a round-the-clock research team, hoping for anything to give their son a chance to live. A biopsy was performed to determine what mutations his cancer had, because the more information, the better they could target clinical studies. Jeni explains that there are around 500 mutations and they found out Buddy had three, one of which is the H3.3, the most aggressive type.

After his biopsy, Buddy underwent 30 rounds of radiation treatment over six weeks. “Buddy had a really hard time with the radiation,” Jeni recalls. “We drove down to Ann Arbor five days a week for six weeks, and he was fatigued. We’d come home and he just wanted to lay on the couch and do nothing.” The treatment was done un-sedated, and Jeni explains, “Buddy had to be strapped into a mask that snapped onto the table so he couldn’t move, and then put into a little tube. It was a scary experience, but he got through it,” she says. But, after the radiation, Buddy bounced back and the “honeymoon” period the doctors had described began. He could run and jump and play, and once his energy returned, the Millers went to Disneyland for their Make a Wish trip, making happy memories as suggested, in preparation for the eventual worst outcome.

A search for clinical trials in the U.S. came up empty, Jeni explains. “There was nothing available in the U.S., so we started looking into studies done in Germany and London. With hope that they would have plenty of options, they applied to participate in all of them, and were turned down by all but one. Either Buddy’s cancer didn’t have the particular mutation that the trial was for, or he was rejected because he already had radiation treatment. “Eventually, we came across a family who had gone to Mexico for a trial,” Jeni says. That was their only option, and they pursued it.

In Mexico, Buddy undergoes intra-arterial chemotherapy. “They go into the artery through the groin and all the way up the spine, directly into the tumor with a drug cocktail,” Jeni explains. “They go through the spine, because if the cancer does not metastasize somewhere else in the brain, it goes into the spinal cord. They are trying to prevent that from happening.” In addition to chemotherapy, Buddy’s treatment also includes immunotherapy. “They take around 20 vials of his blood and send them off to a lab to reprogram them to fight the tumor,” Brad describes. The family attributes huge gains in Buddy’s health to the addition of immunotherapy. “He went from doing good, to doing great after the immunotherapy,” Jeni adds.

In Mexico, Buddy undergoes intra-arterial chemotherapy. “They go into the artery through the groin and all the way up the spine, directly into the tumor with a drug cocktail,” Jeni explains. “They go through the spine, because if the cancer does not metastasize somewhere else in the brain, it goes into the spinal cord. They are trying to prevent that from happening.” In addition to chemotherapy, Buddy’s treatment also includes immunotherapy. “They take around 20 vials of his blood and send them off to a lab to reprogram them to fight the tumor,” Brad describes. The family attributes huge gains in Buddy’s health to the addition of immunotherapy. “He went from doing good, to doing great after the immunotherapy,” Jeni adds.

Amazingly, the treatment has shrunk Buddy’s tumor, so much that it is no longer visible on an MRI. It is visible through PET scans, where you can see activity of the tumor, but the Millers report that they can see it less and less every time. Now, the boy who was given nine months to live after the diagnosis of an incurable and aggressive brain cancer, has made it a year and two months, and counting. The Miller family hopes that he could be the first person to survive it.

But, the treatment is grueling and is taking its toll. Since they are going to Mexico for treatment, none of it is covered by insurance. The Millers have paid over $200,000 out-of-pocket on the treatments alone, not including the cost of travel. All of the funds have been donated and, while the Millers are beyond thankful to everyone who has helped in Buddy’s fight to survive, the battle is far from over.

The family reports that when Buddy first began, he was going to treatment every month, now it is every two months, and they should be able to continue spreading the treatments out further until, hopefully, it is a bi-annual maintenance plan. Brad explains, “with this treatment, we don’t ever see a place where we are done. Maybe in five years, something else will come up – but for now, this is all we have and we are not giving up.”

Brad continues, “we have been extremely blessed by our circle of friends and family who have been so supportive. Not everyone has that. The problem is that it’s getting harder and harder to find the money. When people first hear of the story, it is more shocking – and then, you’ve already given, and people can’t keep giving – we understand that. But, we aren’t stopping until this thing is completely gone.”

The Millers go back to Mexico on April 26 for Buddy’s tenth treatment, and the next one is set for eight weeks later. Jeni says, “spreading the treatments out is great and scary at the same time, because once the cancer goes into progression – if it starts growing – it goes just like that … one day, he might be fine and the next day …” While they are really close to getting Buddy’s cancer down to what is medically rated as “no evidence of disease,” they are watching as other Michigan children with DIPG are lost.

According to Jeni, cases of DIPG are not that uncommon, and they have risen in Michigan from two per year to nine per year. She emphasizes, “We have lost at least four Michigan residents, including a young boy from Flint, just since we have been on this journey. It’s not as rare as people think. Pediatric brain cancer gets four percent of the funding for studies, and DIPG only receives about one percent for clinical trials. So, there are like $500 dollars out there in a year to try and save my son, and they need millions to run a single trial.”

According to Jeni, cases of DIPG are not that uncommon, and they have risen in Michigan from two per year to nine per year. She emphasizes, “We have lost at least four Michigan residents, including a young boy from Flint, just since we have been on this journey. It’s not as rare as people think. Pediatric brain cancer gets four percent of the funding for studies, and DIPG only receives about one percent for clinical trials. So, there are like $500 dollars out there in a year to try and save my son, and they need millions to run a single trial.”

Brad adds, “the biggest thing we want people to know is that we give all the credit to our supporters. We cannot say thanks enough. Without that money, we wouldn’t have any options and we see it happen to people a lot – they can talk about Mexico, but they don’t have the resources. If it weren’t for the help we’ve received and the Lord above, we wouldn’t have anything.”

For more information on Buddy or to contact the family, visit the facebook page dedicated to him, “Team Buddy Boy – Braden Miller, Warrior of DIPG.”

What is DIPG?

- DIPG affects the pons portion of the brainstem, rendering nervous system function impossible. Symptoms include double vision, inability to close the eyelids completely, dropping one side of the face, and difficulty chewing and swallowing.

- DIPG is a rare pediatric brain tumor that typically strikes between the ages of 5 and 7, infiltrates the brain stem, and has a 0% survival rate.

- A child diagnosed with DIPG today faces the same prognosis as a child diagnosed 40 years ago. There is still no effective treatment and no chance of survival. Only 10% of children with DIPG survive for 2 years following their diagnosis, and less than 1% survive for 5 years. The median survival time is 9 months from diagnosis.

- DIPG is so difficult, it is even suggested that a cure to DIPG might result in a cure for almost every other type of cancer.

information from thecurestartsnow.org

“With this treatment, we don’t ever see a place where we

are done. Maybe in five years, something else will come up –

but for now, this is all we have and we are not giving up.”

– Brad Miller

Photography by Jennifer Hodney & Photos Provided by The Miller Family