In the early 1900s, the concept of the human immune system was beginning to take hold in the scientific community. Scientists such as Louis Pasteur, Paul Ehrlich, Elie Metchnikoff and others described a system that our bodies use to protect against attacks by micro-organisms. At first, the immune system was thought to be solely based upon protection. Nobody would have ever thought that the very system that protects the body could also harm it. That is until 1906, when Clemens Von Pirquet, a Viennese scientist, produced a paper entitled, “On the Theory of Infectious Disease.” In it, Pirquet makes the claim that symptoms caused by infection were not only the result of the actions of microorganisms and their toxins, but also the body’s response to them. The revolutionary theory was met with resistance in the scientific realm. Undeterred, Pirquet continued his research and later that same year, would release a now classic article entitled, “Allergie.” The term is derived from the Greek allos, meaning “different” and ergia meaning “action.” He noted that “exposure of the body to a substance resulted in the production of antibodies that induced a change in subject-specific reactivity to the substance.” He also noted that the change can be protective in the case of immunity or harmful in the case of hypersensitivity (if the exposed substance is benign.) In 1911, Pirquet took it one step further and noted that an allergic response is capable of change over time.

Pirquet closely described the phenomenon that results in the formation of an allergy. Today, an allergy is defined as an inappropriate immune response to an otherwise harmless substance in the environment. (Pirquet termed this occurrence hypersensitivity.) Allergies affect millions of people throughout the world and are rapidly becoming more common. A person can develop an allergy to many different environmental factors and allergies can manifest in a myriad of ways, some more serious than others. Hay fever affects nearly 400 million people globally. Food allergies affect over 200 million people while drug allergies impact 10% of the world’s population. The majority of Americans have experienced an allergy of some sort and the number of Americans with allergies is steadily increasing.

An allergy is the result of a “mistake” of the immune system. When the immune system encounters a benign allergen (pet dander, for example), it is usually met with a type 1 response. A type 1 response occurs when regulatory T-cells identify the allergen as harmless. If the body mistakes the allergen (such as pet dander) as harmful, however, a type 2 response could occur. Instead of regulatory T-cells, T-helper cells show up to stimulate the production of antibodies called immunoglobulin (lg) E molecules. These antibodies travel and attach to cells that release chemicals (such as histamine) causing inflammation. The first exposure to an allergen that results in a type 2 response is called allergic sensitization. Your body now becomes primed to produce lgE in large quantities at every future encounter with the allergen. Most people need two exposures to develop allergic symptoms but, on rare occasions, a person can develop an allergic symptom at the initial encounter.

Science currently does not understand the underlying biological mechanism that causes the immune system to mistake a non-threatening invader for a malicious entity. Scientists do understand that the two main factors an allergy needs to develop are exposure and genetics. Exposure is obvious – for one to develop an allergy to pet dander, one would have to be in contact with pet dander. But once exposed, genetics plays a key role in determining whether or not an allergy is developed. A person is more apt to develop an allergy in life if their parent is allergic. For example, if a person has an allergic reaction to pollen (hay fever), the likelihood that their child will develop an allergy is higher than a child with non-allergic parents. Strangely enough, the type of allergy does not transfer from parent to child. For instance, if a person is allergic to pet dander, their child won’t necessarily develop that particular allergy. The child may develop a food allergy, instead. The reason for this is just another mystery that science is striving to solve.

An allergy is defined as an inappropriate immune response to an otherwise harmless substance in the environment.

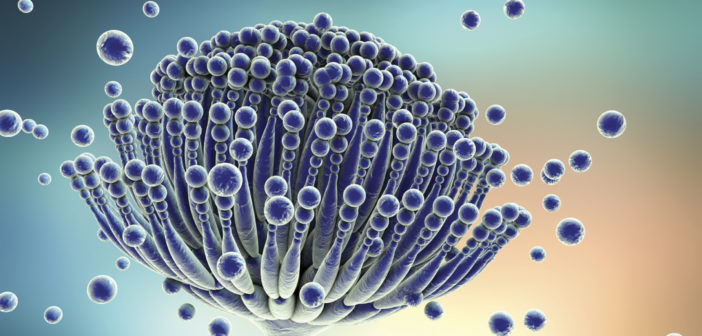

People are not born allergic. As stated above, an allergy develops due to exposure to outside stimuli. A person can develop an allergy to food – shellfish, milk, eggs, peanuts, etc. – medicines, insect-stings, pollen, pet dander, mold, dust mites, fungi and cockroaches, to name a few. The severity of the allergy can also fluctuate depending on the individual. An allergy can also develop at any time throughout life, with manifestation most often in children. Some can be outgrown, such as dairy, egg and shellfish allergies, while some are lifelong, such as allergy to nuts or pollen.

Recently, allergies are becoming much more prevalent in the U.S. and around the world. Science currently recognizes two ideas as to why. The “hygiene hypothesis” implies that our hyper-sterile environment is hampering our bodies’ ability to tell a harmful allergen from a harmless one. The theory is supported by research of animals and some human test groups. Preliminary evidence has been convincing, causing some scientists to state that cleanliness should be practiced in moderation, especially with children. For example: It’s okay for kids to get dirty outside and to run around with bare feet – it should be encouraged. Research also points to global climate change as another cause for the rise in allergies, with growing pollen and spore levels increasing our exposure. Symptoms of an allergic reaction and their severity are determined by type of allergy and the body chemistry of the allergic individual. For instance, no two cases of hay fever (pollen allergy) are exactly the same. Symptoms of a reaction include: sneezing, hives or rashes, swelling, vomiting, diarrhea, bloating, cough, feeling faint, chest tightness or, in very severe cases, asthma and anaphylactic shock.

Most Common Allergies

Food: Food allergies affect roughly 6% of children and 4% of adults, most common in babies or children but can appear at any age throughout life. You can suddenly develop an allergy to a food that you have eaten your entire life without harm. The most common problem foods are shellfish, eggs, milk, peanuts, fish, wheat and soy. Symptoms of a reaction typically begin about two hours after digestion, but can occur immediately. They tend to be severe and include anaphylaxis, a life-threatening, whole body reaction that can impair breathing and drastically reduce heart rate. It can be fatal if not treated promptly with a dose of epinephrine (adrenaline).

Hay Fever (Allergic Rhinitis): The most common allergy, this is typically a reaction to something non-threatening in the environment such as pollen, dust mites, pet dander or mold. Symptoms vary in severity and include runny nose, itchy eyes, sneezing, fatigue or asthma. This allergy can either be seasonal (sensitivity due to spores of pollen in spring or fall) or perennial (year-round due to triggers such as dust mites or pet dander.)

Contact Dermatitis: When the skin comes into contact with an allergen, reactions can include rash, hives or, in extreme cases, eczema. Soaps, plants, fabric softeners, shampoo, latex, adhesives and even metals can cause allergic reactions.

Insect-Stings: While not as common as most other allergies, this can be extremely dangerous. At least 100 deaths per year are attributed to insect-stings, typically wasps, yellow jackets, hornets, honey bees and fire ants. Symptoms of reaction tend to be severe and include pain, swelling, itching, hives or anaphylaxis.

Drugs: Drug allergies are taken very seriously in a medical setting. The most common include penicillin, certain antibiotics, aspirin, ibuprofen and chemotherapy drugs. Symptoms include rash, hives, wheezing, swelling and anaphylaxis.

If you suspect that you may be suffering from an allergy, visit your local allergist for testing. The process involves a skin test or a blood test. During the skin test, a drop of allergen is pricked on the back or the back of the arm. If you are allergic to the allergen, redness or swelling will occur. Results of the test typically appear in an average of 20 minutes. A blood test is generally only used in cases of eczema or psoriasis, or when a person is on medication that could affect a skin test. It may take days or weeks to receive blood test results.

Treatment

Epinephrine (Epi-Pen® Auto-Injector): The most important treatment for anaphylaxis, epinephrine (adrenaline) is available in a single dose, pre-filled injection device that must be administered within minutes after the first sign of anaphylaxis to relax the airway muscles and tighten the blood vessels.

Medicine(s): Some drugs are made to counteract the most common allergic reactions. Antihistamines, nasal corticosteroids and decongestants can reduce swelling and calm sneezing, runny nose, itching and hives. Corticosteroid creams or ointments can relive skin itching and stop the spread of rashes.

Immunotherapy: Some people get relief from allergy symptoms with immunotherapy, which can be delivered via injection or sublingually. Immunotherapy involves taking an increasing dose of an allergen over time, which can decrease one’s sensitivity to the allergen. Immunotherapy can effectively treat allergic rhinitis or insect-sting allergies. An allergist should be consulted before entering immunotherapy.

Aversion: Sometimes the best treatment is to avoid the allergen altogether. This works best with food, drug and skin allergies.

As allergies become more common, it becomes important for science to continue its research into the phenomenon and for people to understand allergy and its treatment.

References

American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. (2014). Types of allergies. Retrieved from acaai.org/allergies/types

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of American. (2019). Allergy treatment. Retrieved from aafa.org/allergy-treatments/

Hewings-Martin, Y. (2017). How do your allergies develop? Medical news Today. Retrieved from medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319708.php

Igea, J. M. (2013). The history of the idea of allergy. Allergy, 68, 966-73.

Okada, H., Kuhn, C., Feillet, H. & Bach, J. F. (2010). The hygiene hypothesis for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 160, 1-9.

Petti, L. (2016). Allergies are on the rise, and here are three reasons why. CNBC. Retrieved from cnbc.com/2016/09/09/allergies-are-on-the-rise-and-here-are-three-reasons-why.html

Zimney, E. (2018). Growing into and out of allergies. Everyday Health. Retrieved from everydayhealth.com/asthma/webcasts/growing-into-and-out-of-allergies.aspx

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of American. (2019). Allergy treatment. Retrieved from aafa.org/allergy-treatments/

Hewings-Martin, Y. (2017). How do your allergies develop? Medical news Today. Retrieved from medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319708.php

Igea, J. M. (2013). The history of the idea of allergy. Allergy, 68, 966-73.

Okada, H., Kuhn, C., Feillet, H. & Bach, J. F. (2010). The hygiene hypothesis for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 160, 1-9.

Petti, L. (2016). Allergies are on the rise, and here are three reasons why. CNBC. Retrieved from cnbc.com/2016/09/09/allergies-are-on-the-rise-and-here-are-three-reasons-why.html

Zimney, E. (2018). Growing into and out of allergies. Everyday Health. Retrieved from everydayhealth.com/asthma/webcasts/growing-into-and-out-of-allergies.aspx