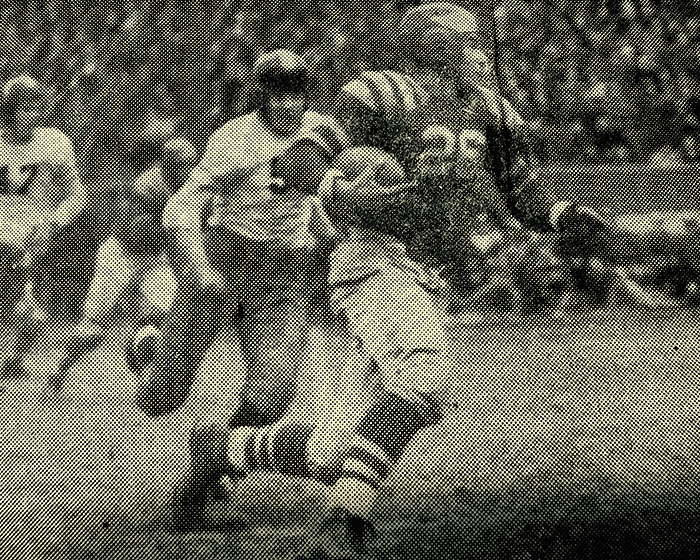

Northern’s Eddie Krupa heads for the end zone in 1940.

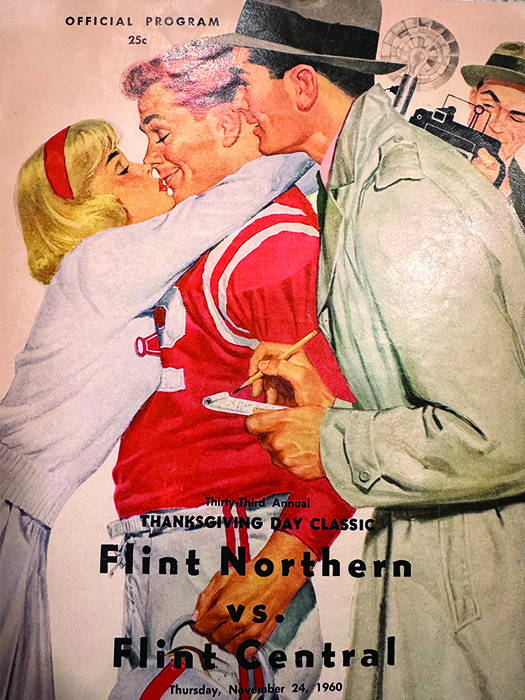

“Every Thanksgiving morning, for nearly half a century, two schools — Flint Central and Flint Northern — met on the gridiron for one of the fiercest and most beloved high school football rivalries in Michigan history.”

Before the parades and pumpkin pie, before families across Flint sat down to eat, there was one thing that brought the entire city together, even as it divided it: the Thanksgiving Day Game.

Every Thanksgiving morning, for nearly half a century, two schools — Flint Central and Flint Northern — met on the gridiron for one of the fiercest and most beloved high school football rivalries in Michigan history.

It wasn’t just a game.

It was a Flint institution.

Turkey and Football

Flint Central was the city’s oldest high school, its red and black colors a badge of honor for generations. It sat on Crapo Street, near the heart of the city, and its alumni included politicians, business and entertainment industry figures, athletes, and the auto workers who built Flint’s backbone.

Northern was eventually built in response to Central’s overcrowding (4,000 students) and the city’s booming population during the auto industry’s heyday. But even before Northern’s construction, Central had a long-standing Thanksgiving football tradition.

The very first Flint Central Thanksgiving Day game was played against Durand in 1902 — a 27-0 Durand victory. In those early years, Central was anything but a powerhouse, losing every Thanksgiving Day game for the next 11 seasons against a variety of opponents.

That changed in 1914 when Central fielded its first dominant team, outscoring opponents 326-45 and defeating Bay City Eastern 18-0 on Turkey Day.

From 1902 to 1927, Bay City was Central’s most frequent Thanksgiving rival, followed by teams from Ann Arbor, Detroit, Lansing, Battle Creek, Fenton, Lapeer, and even the Michigan School for the Deaf.

Central’s program grew into one of the premier powerhouses in the state, playing for Michigan state championships in the pre-playoff era. Back then, the title was decided in a final game between the top team from Detroit and the best team from outside the city.

Central played in four of these championship games between 1908 and 1924, winning twice — in 1923 and 1924.

The Rivalry Begins

Then came 1928. Flint Northern opened its doors to serve the city’s North Side — and immediately became Central’s exclusive Thanksgiving rival.

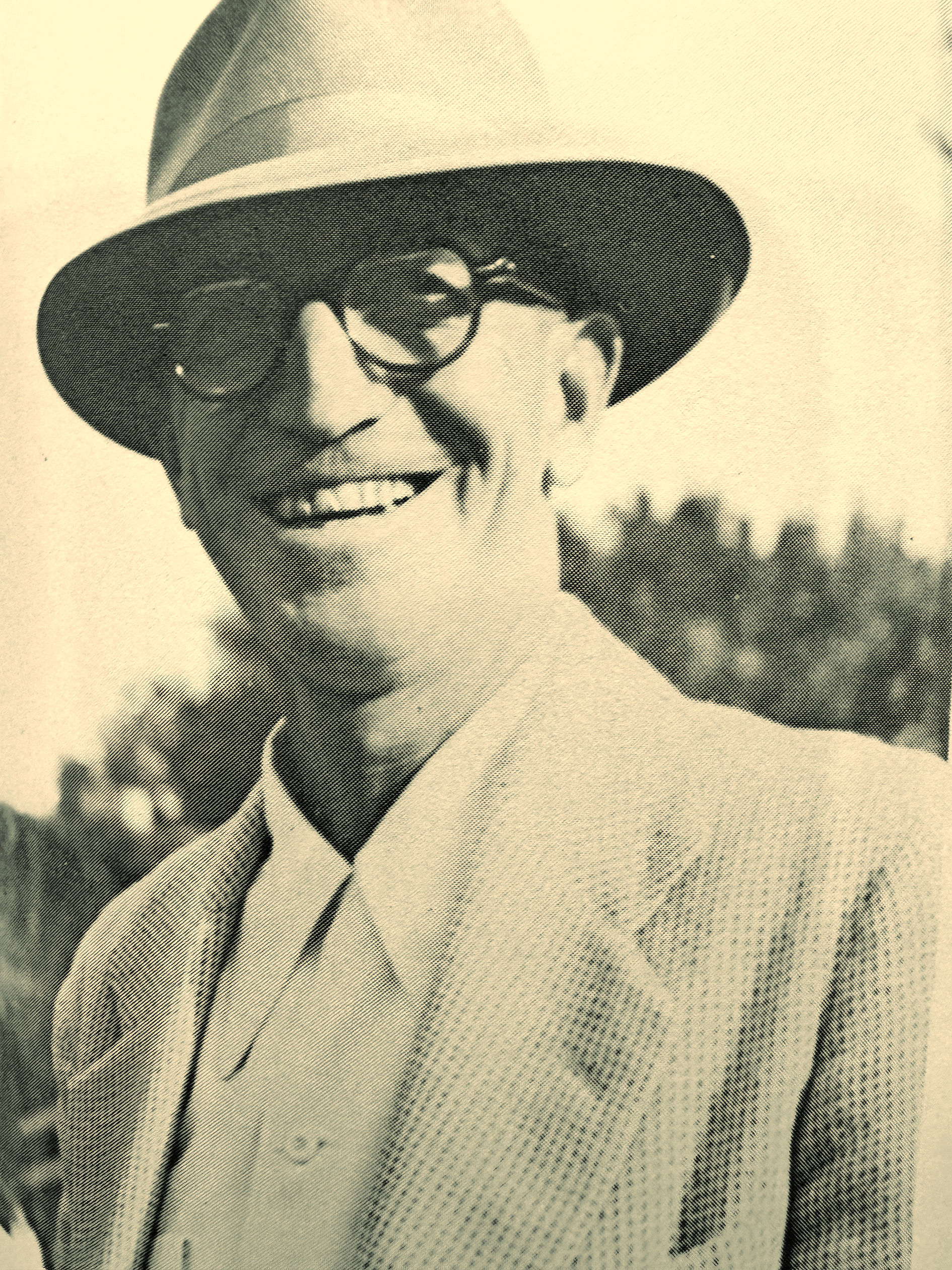

Central superstar and future NFL player, Lynn Chandnois

The intensity, talent, and significance of the game ramped up. It became more than a football game — it reflected neighborhoods, traditions, pride, and the city’s competitive spirit.

Once a year, on Thanksgiving morning, that rivalry exploded onto the field.

It became known simply as: The Turkey Day Game.

More Than a Game

To outsiders, it was just high school football.

To Flint, it was everything.

The game was traditionally held at Atwood Stadium, a grand venue nestled along the Flint River. Atwood had hosted college and semi-pro games, but on Thanksgiving, it belonged to the city’s youth — and to history.

The air was always cold, sometimes brutally so, but fans still came out by the thousands. Parents, students, alumni, and former players packed the stands — wrapped in blankets, sipping hot chocolate, stomping their feet against the concrete bleachers to stay warm. For some families, it was the first stop of the holiday. For others, it was the holiday.

Central superstar and future NFL player, Lynn Chandnois

Central’s Harold “Hacksaw” Kaczinski eludes a Northern defender – 1939

“This was bigger than Christmas to some people,” said one former player. “You didn’t miss the Turkey Day Game — not if you cared about Flint football.”

The first Thanksgiving matchup between Central and Northern took place in 1928 in front of 8,000 fans at Dort Memorial Field on Central’s campus — a Northern victory.

Legends Were Born Here

Over the decades, the game produced countless legendary moments — and players. Kids didn’t just dream of playing varsity. They dreamed of starting on Thanksgiving Day.

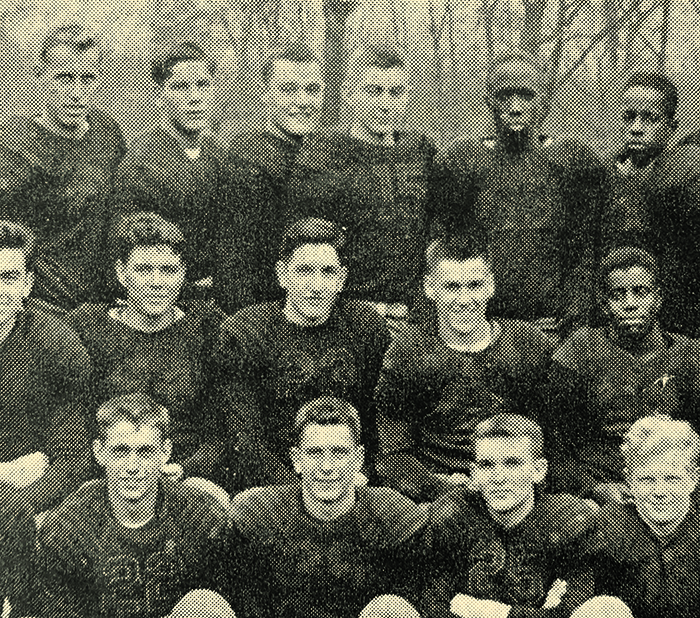

Central’s Hank Minarik (far left) and Jesse Thomas (far right) – future NFL bookends on the 1946 team

There were games in blizzards.

Games on sheets of ice.

Games in ankle-deep mud (before Atwood had AstroTurf).

Games with last-second field goals.

Games decided by a single fumble or a last-second touchdown.

But the stories weren’t just about scores. They were about grit, pride, and community. Coaches like Guy Houston at Northern became father figures and legends. Houston led the Vikings to 10 unbeaten seasons and multiple state titles. Teammates became lifelong friends. Opponents became respected adversaries.

“Over the decades, the game produced countless legendary moments — and players. Kids didn’t just dream of playing varsity. They dreamed of starting on Thanksgiving Day.”

Northern was, after all, born from Flint Central DNA. Many of the players became lifelong brothers. The memories, shared for generations, were among the most cherished of their lives.

“Playing in that game … it made you feel like you were part of something sacred,” said a Northern alum. “You were playing for your school, your side of town, your people.”

Many players became stars at the collegiate level and in the NFL.

A Short List of Legends (1928–1976)

Flint Central:

- Lynn Chandnois – NFL

- George Guerre – MSU

- Don Coleman – MSU

- Steve Bograkos – NFL

- Clarence Peaks – NFL

- Tony Branoff – University of Michigan

- Joe Ponsetto – University of Michigan

- Jesse Thomas – NFL

- George Hoey – NFL

- Hank Minarik – NFL

Flint Northern:

The “Wonder Boys” – Known for going unbeaten in football and basketball, setting a state record for longest basketball win streak, and winning multiple championships:

- Eddie Krupa (Notre Dame)

- Len Sweet

- Bob Holloway

- Dick Holloway

Krupa’s career was cut short during World War II when he was wounded as a Marine on Iwo Jima. Sweet, considered the most gifted of the group, suffered a serious illness before graduating.

Other standouts:

- Ellis Duckett – MSU

- Leroy Bolden – NFL

- Leo Sugar – NFL

- Art Johnson

- Russ Reynolds

Tradition Runs Deep

For many families, the rivalry was generational. A grandfather might have played for Central in the 1920s, his son in the ’40s, and his grandson in the ’60s.

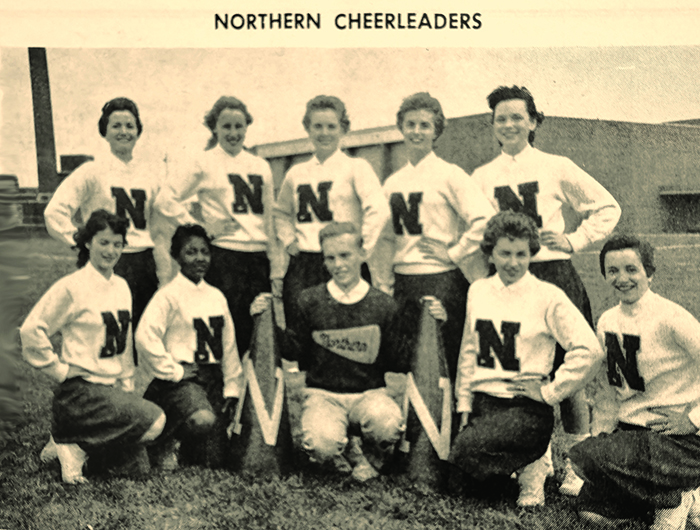

The Monday before the game, schools erupted with Spirit Week energy. Huge pep rallies shook the gyms.

Students painted their faces, decorated lockers, and waved signs that read “Crush the Vikings!” or “Scalp the Indians!”

Hallways turned into battlegrounds of pride. Alumni came home. News crews rolled into town. The entire city buzzed.

On Thanksgiving morning, the crowd would file into Atwood. The marching bands from each school paraded across town to the stadium. Announcers crackled through the cold air. Cameras clicked. Film rolled. The game began.

Attendance sometimes topped 20,000.

The End of an Era

The final Thanksgiving Day game took place in 1976 — a Central victory.

The introduction of the Michigan high school playoff system marked the end of the tradition, as it created scheduling conflicts. But in truth, the rivalry had already been diluted by the opening of Flint Southwestern (1959) and Flint Northwestern (1964), which split loyalties and diluted the talent pool.

Though attendance declined (by historical standards), it still dwarfed crowds seen today.

The game — and the schools themselves — are now gone, but the spirit of the Turkey Day Game lives on. It lingers in newspaper clippings, family stories, barbershop debates, faded photos, VHS tapes, class reunions, backyard BBQs — and most of all, in the hearts of those who played, coached, or cheered.

Still Remembered

Every Thanksgiving morning, some old-timers still drive past Atwood Stadium. And if you listen closely, you can almost hear the bands, smell the hot dogs, feel the cold bleachers, and remember sitting next to your dad or shouting next to your friends on the wall.

You remember the big play.

The big moment.

The way it brought a whole city together.

For just a few hours every year, football, family, and the spirit of Flint were one and the same.