My City Magazine is excited to present various historical series that will capture both the whole and the details of eras past. These features will explore Flint’s rich history, including its famous inhabitants, historic buildings, its changes and contributions to society.

Our first series – “The Automotive Years” – takes an in-depth look at the rise of the automobile in Flint, beginning with its predecessor, the carriage. These stories will include biographies of notable figures including William C. Durant, J. Dallas Dort, C.S. Mott and Alfred Sloan.

Pretend while you read that you are not ensconced in the comforts of the 21st century; try to climb inside these snapshots of Flint at a different time and see these people as more than ghosts. Join us in discovering the heritage of Flint!

William Crapo Durant is Flint’s hometown hero. His legacy includes famous companies that put Flint on the map; but there is so much more behind his contribution to Flint than the two words General Motors. In fact, Durant’s first vehicle was not an automobile at all: it was a carriage. Let’s take a look at Durant’s beginning to see how his personal work ethic and the carriage precipitated Flint’s nickname: Vehicle City.

Billy Durant was the grandson of a famous Flint timber baron and the son of an infamous drunkard. Although he was a bright student, he quit high school to go to work at his grandfather’s lumber yard in 1877. He worked multiple jobs at that time, including selling medicines and cigars door-to-door, and met with great success. At the time of his marriage to Clara Pitt in 1885, Billy was already a prominent citizen and owner of several businesses. Durant’s fate—and the fate of Flint—would change a year later when he took a ride in a small, frail looking buggy.

The buggy provided a smooth ride, despite its appearance, thanks to an innovative suspension system. The very day following his ride, Billy bought the company that had built the carriage. Upon hearing about the new venture, his good friend, J. Dallas Dort, whom Durant described in his notes as “one of the best men that ever lived,” immediately quit his contract in the hardware business and bought a half interest in Durant’s company. Billy, a salesman at heart, took one of the two carriages he had just purchased to a show in Madison WI, and returned home with 600 orders in his pocket. William Pelfrey, author of Billy, Alfred and General Motors says that at this time, Durant “and partner Dort had not yet built a single cart, nor did they have a shop or factory in which to build one.” It is easy to imagine how persuasive Billy Durant was, given this history of his early years and the beginning of his carriage business. The Flint Road Cart Company, as it was originally named, seems to have been founded entirely on Durant’s charming sales ability.

It wasn’t just Durant’s salesmanship, however, that helped the company to thrive: it was his innovation in the production of the carriage. These innovations, driven by necessity, shaped the corporate world and the automotive industry in particular, in ways that are still visible today. First, Durant’s new company used the world’s first vehicle assembly line, creating a cost-efficient road cart that could be produced quickly in order to maximize profit. There is no question that the assembly line was integral to the automotive industry’s explosion in the early 20th century, but many people do not realize that Durant and Dort used the assembly line for their carts 30 years before Henry Ford used it for his car.

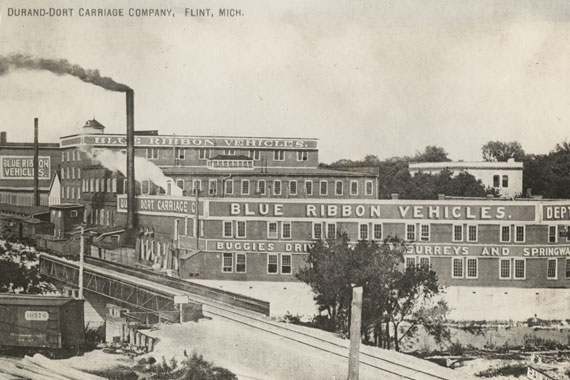

The second major innovation that Durant introduced to the corporate world was the idea of vertical integration. Vertical integration is the merging of separate businesses in different phases of the production of a single commodity. In 1895, Durant learned the value of owning all phases of production the hard way, when he lost clientele to William A. Paterson, the man who was building Durant’s ‘Famous Blue Ribbon Line’ of carts at the time. Paterson learned that Billy was selling the cart for almost double what he paid Paterson, and so Paterson made a pitch to one of Billy’s clients, offering to sell him the carts at a lower cost. The partners immediately ended their business with Paterson and moved their operations to an abandoned woolen mill on the banks of the Flint River. They changed the name of their company to Durant-Dort Carriage Company, but that isn’t the only change they made. In addition to vertical integration, Durant’s company began to offer a variety of models of the same basic product (the Standard, the Victoria, the Moline, and the Diamond), which allowed for high-volume, standardized production. He also developed modern franchising, which involved a national network of dealers. Pelfrey says that although Durant never received any credit, in redefining the carriage industry he created a strategy that became the business model for the entire automobile trade and dozens of other industries for most of the twentieth century.

By 1900, Durant-Dort was the largest vehicle manufacturer in the United States, and Billy Durant was known as “King of the Carriage Makers.” Flint enjoyed the economic benefits of Billy’s hard work. At its height, the Durant-Dort Carriage Company owned eight factories in Flint, making it the city’s largest employer. The industrial plants, thanks to Durant’s keen attention and the relatively easy working environments, were free from the riots and unionization efforts that characterized the nation as a whole in this historical period. There is good reason indeed, for the Durant name to be so deeply ingrained in the Flint subconscious!