Every hour, over 100 infants die from hypothermia – 140, to be exact. Worldwide, almost four million infants die each year during the neonatal period (0-27 days) in areas where hypothermia is a leading cause of mortality.* The good news: something is being done about it, right here in Michigan.

Kettering University’s Dr. Uma Ramabadran and Dr. Gillian Ryan are helping with research for Warmilu, LLC, an advanced therapeutic warming technology start-up company in Ann Arbor, to continue improving a specific technology used to make non-electric heated blankets.

Kettering’s Physics Department has worked with Warmilu since November 2013, establishing tasks that could be done at Kettering with their research facilities and equipment. September 2011 is when Warmilu first assembled the team and conceived the idea of non-electric warming technology for use in infant warming; they had a working prototype by March 2012.

Grace Hsia, Warmilu CEO and co-founder, has a passion for this line of work. “When you look at the epidemiology of 15 million annual preterm births, pre-term birth is a risk factor for neonatal and post-neonatal deaths,” Hsia explains. “At least fifty percent of all neonatal deaths are preterm.” In addition, this line of work hits close to home. “I was born preterm,” she shares. “So, this really resonated with me.”

The countries with the highest estimated numbers of preterm births are India, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, Indonesia, United States, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Brazil. These ten countries account for 60 percent of all preterm births worldwide.

“We found that given the successful preliminary conversations with doctors, nurses and volunteers from India, Haiti, Chile, Kenya, China, and the U.S. that we were best positioned to target India given our team bandwidth and personnel at the early stages in 2012,” Hsia says. Beginning in January 2013, Warmilu sent IncuBlankets to community centers, hospitals and specific towns and villages in Kenya, Chile, Kazakhstan, the U.S., as well as India.

Warmilu frequently follows up with the neonatologists, nurses, and volunteers for updates about patients they treat, but gathering that information can be a challenge. “Not everyone goes back to the hospital for a recommended check-up,” says Hsia. “We’re looking to get better connected to the follow-up care part of the value chain.”

Warmilu works with non-profit distributors, such as Relief for Africa, and sometimes works alongside their distributors and medical partners in the field. The company will travel to Kenya this March to launch Warmilu’s IncuBlanket showcase to fifty Ministry of Health officials.

While Warmilu does the dispersing of IncuBlankets in villages and hospitals around the world, Kettering continues research to improve the product. “We are looking at it from two different angles,” explains Dr. Ramabadran. They are trying to slow down the production of heat during phase transition (liquid to solid). The material they are working with is similar to that used in hand-warmers you can currently buy. It would be a super-saturated solution, which could be triggered and would then crystallize, thus releasing heat.

In commonplace hand-warmers, all of the possible heat is released instantly. “We are looking at adding components to the material to slow down and release the heat over a longer period of time,” Ramabadran says. Materials that could be added to slow the heat release include paraffin waxes and different oils to create physical barriers to the crystal growth and hold in the heat. Another way to slow the heat release is to change the way the crystals grow; this is something Dr. Ramabadran and Dr. Ryan are pursuing.

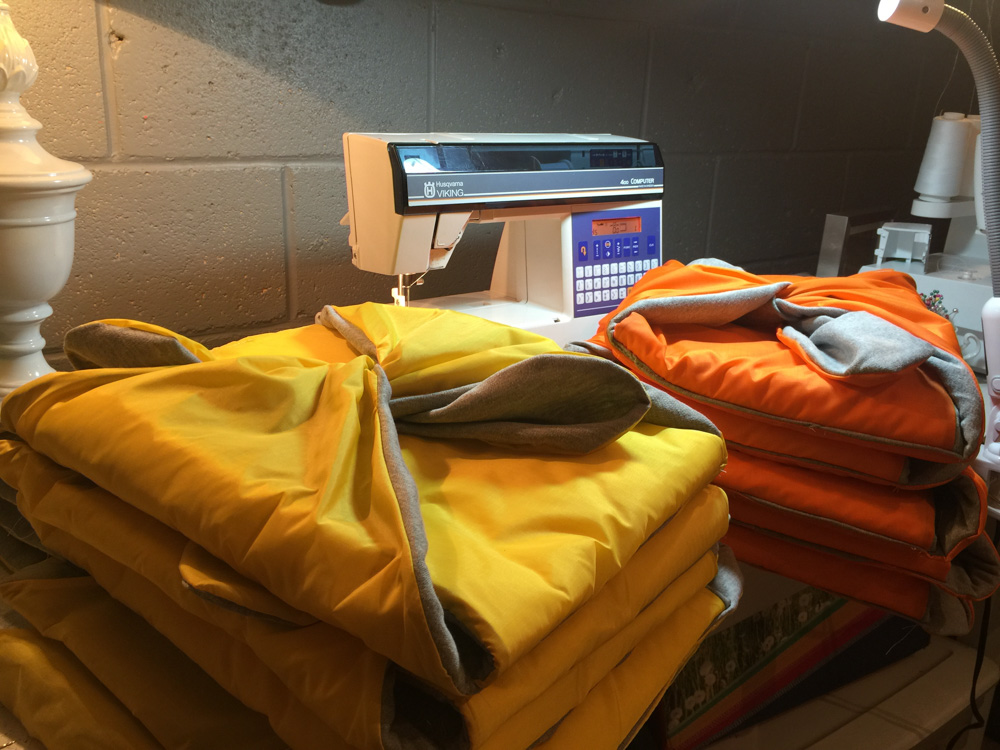

The IncuBlanket can keep an infant warm for up to five hours; all caregivers need to do is activate it by placing it in boiling water. Currently, the researchers’ goal is for the heat to last for eight hours – a full night’s sleep. “You can reuse them about a thousand times,” says Dr. Ramabadran. Their second obstacle is that they do not want the blankets to get too hot too quickly. The temperature cap is 36-37 degrees Celsius (about 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Researchers measure the rate of crystal growth using a high-speed camera and software to view how the crystal propagates.

Materials used in this technology are not limited to blankets for neonatal care. “This could have all kinds of applications,” Dr. Ramabadran says. One Kettering student thought that this material could be used in underwater diving suits, although that experiment has not yet been done. The blankets can also help with chronic pain management, internal medicine, and physical therapy for people with arthritis or diabetes. “We have a much higher level of feedback on our warming packs used to treat chronic joint pain,” Hsia says.

To further this research, Kettering University is using equipment they received through a grant from the National Science Foundation, like the X-Ray Diffractometer, which measures the atomic structure of the warming crystals. Another device Dr. Ramabadran uses is a desiccant chamber – an electric humidity controller – which helps her control the amount of water in different materials in various trials.

“It has been game-changing to see how a blanket or a pack changes and creates new mobility for doctors, nurses and volunteers, and heightened access to life-saving warmth,” Hsia says. Currently, Warmilu is leveraging the connections at The Manufacturing Institute and Forbes’ 30 Under 30 Summit in Washington D.C. and Tel Aviv, Israel to grow their plan for breaking into new markets.

The world’s infant mortality rate is still very shocking; but because of the ongoing research at Kettering University and the implementation techniques set by Warmilu, that number will someday decrease, and they will continue to spread warmth and save more lives.

For more information, visit warmilu.org.

Photography By Mike Naddeo & Provided By Grace Hsia

*WHO Reproductive Health Library