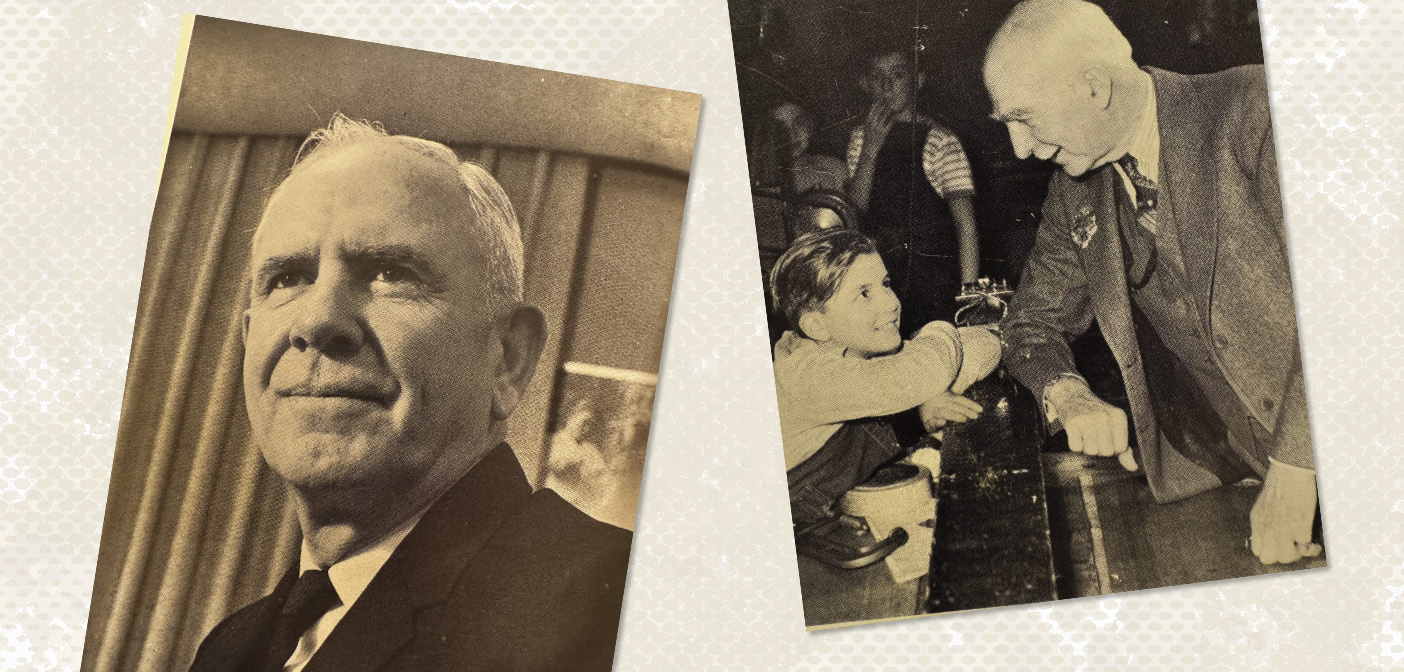

Frank Manley

The “big idea” started in 1923 with physical education instructor Wilbur P. Bowen. In his class was a young man named Frank Manley, who absorbed every single word and philosophy that Bowen put forth. Chiefly among those ideas was the notion that athletics was such an enormous social good, that it was a key to living a quality life and paramount to the good of the community. Bowen even laid out the plan that would have to be in place to properly implement that in a community. He said that the cornerstone was the notion that all community facilities be made available for recreational activities and sports.

As he laid down the foundation of his ideas in class, the rapt Manley took careful notes. Bowen expanded on his plan by making it clear that people needed to have an outlet to express themselves, and a chance to shine as individuals. He posited that if all of that were in place, people would gravitate to the positive side of the moral equation of life, and if done early enough, they would retain this moral compass and continue to act proactively and morally for the balance of their lives.

Manley believed this whole heartedly because he had lived it growing up in relative poverty in Herkimer, New York. His mother died when he was ten, and his father was riding herd on a failing livery business that the new automobile industry was slowly strangling out of existence. Whether it was anger, depression or simply being too distracted, he didn’t care or comment when young Frank started skipping school and heading down the wrong path. Manley finally made it official and dropped out completely in the ninth grade.

It was football that saved his life.

His pals urged him to come back to school so he could play football, and he did just that for four years. Along the way, he realized he had to stay eligible to continue to play – so he refocused on academics. It was this experience that proved to him that for many kids, sport was an antecedent of academic success, not a reward for academic performance.

Football fueled Manley’s success and he headed off to college. It was there that another critical role model appeared in the form of Professor Charles M. Elliott, head of the Special Education Department at Michigan State Normal College.

Elliott preached that everyone should be treated as an individual. He emphasized that it didn’t matter who they were: Jew, Gentile, Black or White, capitalist or laborer, or how old they were – they were all unique individuals and should be treated as such. That was heady and progressive stuff for the 1920s!

When Manley graduated, he found employment in the city that would prove to be the perfect laboratory for his now closely-held beliefs: Flint, Michigan.

In 1923, Flint was booming. Flint’s own William C. “Billy” Durant had saved and nurtured the Buick company, parlayed that into single-handedly inventing General Motors and later Chevrolet, Champion Ignition (later AC Spark Plug), Frigidaire, and rolling Oakland (later known as Pontiac) and Cadillac into one giant manufacturing success story. By the time Manley got to Flint, Durant had left GM and started a self-named auto company – Durant Motors. In Flint, all of those factories had learned early on that if you want to bring people together, get them involved in athletics, particularly team sports.

So, the world that Manley encountered in Flint was brimming with success and athletics, and eager for just the kind of spirit a man like he would bring. He started his teaching career at Whittier Junior High School, then went on to Flint Central High School, and also directed the phys ed programs at the elementary school level. At Central, he walked into a sports powerhouse, and in Flint – a city already loaded with talent of every type. The city loved Manley and his ideas, and he soon oversaw phys ed for the entire Flint Public Schools system.

Manley’s first big project was to create a Sportsmen’s Club at Martin Elementary, which led to the establishment of clubs at two other schools. Soon, other schools were clamoring for the same. Just as Manley and his programs were starting to ratchet up, the nation surged into the Great Depression. And just like that, everything changed for the worse in Flint, especially for the kids.

Traffic accidents with children soared, drownings in the Flint River and city pools increased, and juvenile delinquency and crime rates rose dramatically. Manley dove into the problems. He immersed himself in the court system and soon had a roster of 90 kids on probation assigned to him. He went out on patrol with the Flint City Police to the roughest areas of the depressed city, organized his parolees into an athletic club – and watched them transform.

In short order, everything he had believed in was being proven true. The problem was that he didn’t have the means to implement or scale it. So, he started a speaking tour to convince the “big men” of Flint business of the necessity and efficacy of his community-minded recreation and athletic ethos. He found a wall of silence and disinterest from nearly all of them – nearly, but not all. One man was intrigued. His name was Charles Stewart Mott.

Charles Stewart Mott

At the invitation of Billy Durant, Charles “C.S” Mott came to Flint in 1905. Mott’s company, Weston-Mott, was making axles for Buick (among other brands) and Durant knew he needed vertical integration to make his Buick plant more efficient. Mott and his partner William Doolittle agreed, moved to Flint and joined forces with the Durant-powered dynamo. Doolittle sadly died of stomach cancer shortly after relocating to Flint, leaving Mott as the sole owner. When GM bought out Weston Mott, Mott became one of the richest men in the U.S. and a GM board member (a role he held for an astounding 60 years).

By the time Mott heard Manley speak, he was the kingpin of Flint – supplanting both Durant who had gone bankrupt in the Great Depression, and Durant’s former partner J. Dallas Dort (known as “Mr. Flint”) who had died of a sudden heart attack. Mott not only emerged as the second wealthiest Flintstone ever (behind only Durant himself when he was on top of his game), he was also the most engaged politically, serving twice as Mayor of Flint. Dort had started a tradition of providing for the good of the community by establishing the Industrial Mutual Association (IMA). He was also an avid sports fan and golfer, and the notion of Manley’s ideas resonated with him.

Frank Manley started a speaking tour to convince the “big men” of Flint business of the necessity and efficacy of his community-minded recreation and athletic ethos. He found a wall of silence and disinterest from nearly all of them – nearly, but not all. One man was intrigued. His name was Charles Stewart Mott.

His untimely death left a void that Mott strode into – unexpectedly, as Manley saw it.

That was because Manley had heard that Mott was very “Scotch” which was an early 20th century pejorative meaning “cheap.” Luckily for Manley (and for Flint), that proved to be quite false. Indeed, Mott would prove to be one of America’s great philanthropists in short order, and a case can be made that Frank Manley was the progenitor of the art that would be known as “community education.”

After hearing Manley speak, Mott invited him to his Flint mansion, Applewood, ostensibly to play tennis. Instead, he was checking Manley out. Multiple days of tennis playing ensued, leading up to Mott asking him what he thought about establishing a boy’s club in Flint. Manley jumped at the chance to expand on what he had been preaching all over Flint and living in his own life and profession. He told Mott, “That’s a great idea; but instead of building something, let’s use the 40 boys clubs we have in Flint right now – all these unused schools. These buildings have gymnasiums, cafeterias and classrooms; they’re heated in the winter, well lit, and they could be instant boys and girl’s clubs.”

Mott agreed to start with five schools and build from there. In short order, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Program of the Flint Board of Education was born. The idea expanded to include dental and health care, free lunches, paid coaches and supervisors who soon became known as directors of the program (ultimately known in later years as the Mott Community School Program). Mott provided the money and Manley provided the leadership.

The program built on the already strong adult athletic structure in the city that was fostered by the GM athletic programs to build an equal powerhouse of youth. The massive influx of workers and people post-WWII created the chemistry for what is without question, the greatest athletic dynasty per capita in American history in Genesee County. It led directly to the creation of the Flint Olympian and CANUSA Games, which is now the longest running international athletic competition (between Flint/Genesee County and metropolitan Hamilton, Canada) in the world.

The peak of the program was the ’70s and ’80s when thousands of kids participated in various Mott and community education-based programs. Longtime community school director (1969-1988) at Brownell and Washington Elementary Schools, Jim Whitinger, remembers how impactful the programs were. “We established a community advisory council at Brownell, which had the highest property crimes in the city at the time. Along with that, we created 21 Block Clubs in conjunction with the Flint Police (following the long-established Manley formula). By the time we were done, Brownell had the lowest neighborhood crime rate in the city.”

There were four people who were the cornerstones of the implementation of the entire program, and without whom the entire amazing idea would not have become the envy of the world (that’s not an exaggeration, as educators from around the globe made pilgrimages to Flint to learn the secret sauce of the program).

One can only hope that somewhere, someday, someone with a similar vision meets someone with a big heart and exceptionally deep pockets – and together they can weld their superpowers to change the world, yet again.

These four were Myrtle Black, Alton Patterson, Harold Bacon and former Flint Central football star Bill Minardo. All were critical in executing and memorializing the vision of Manley and Mott.

Over the coming decades, an ensuing roster of legendary Community School Directors (CSDs) would ensue. One of those, Dan Berezny, had life-altering experiences at Homedale Elementary where he started in 1977. He worked hard to build up athletics and community spirit in one of Flint’s poorest and toughest neighborhoods. “We focused on community engagement for everyone in the neighborhood,” he recalled. “It wasn’t just for the kids; we had a big parent’s program and a particularly large senior citizen program.” When asked what was the biggest value the community education concept brought to the area, he was quick to respond, “It was definitely the kids who came up to say ‘thank you – the program probably saved my life’.”

In the late ’70s, the Community Education idea began to die when the Mott Foundation started to pull back financial support from the Flint schools. Soon, the massive economic disruption that resulted from the demise of the auto manufacturing infrastructure, poor leadership and dramatic socioeconomic, and geopolitical events killed the program outright by the ’90s.

In its wake were community-level problems that Manley and Mott could scarcely imagine. The once vaunted Flint athletic tradition is but a memory, with athletes having moved far and wide or attending suburban, private or parochial schools in metro Flint and Detroit.

The perfect partnership of Mott and Manley, the Compassionate Capitalist and the Community Athletic Activist, are fading memories in a city beset by monumental challenges. However, as archaic as their simple but brilliant plan may seem today, it is hard to argue against the beauty of its results. One can only hope that somewhere, someday, someone with a similar vision meets someone with a big heart and exceptionally deep pockets – and together they can weld their superpowers to change the world, yet again.