PHOTOGRAPHY BY RAYFORD GRAY

Through Mindful Movement with Shanzell, the dancer and educator invites students to listen deeply, move intentionally, and find their place within a centuries-old tradition

Rooted in Flint and shaped by rhythm, lineage, and community, Shanzell Q. Page’s work as a tap dancer and educator reflects a lifelong commitment to movement as both cultural practice and shared language.

Shanzell, 39, is originally from Flint and now based in Detroit. She is a tap dancer, educator, and the founder of Mindful Movement with Shanzell, an initiative grounded in cultural history, musicality, and access.

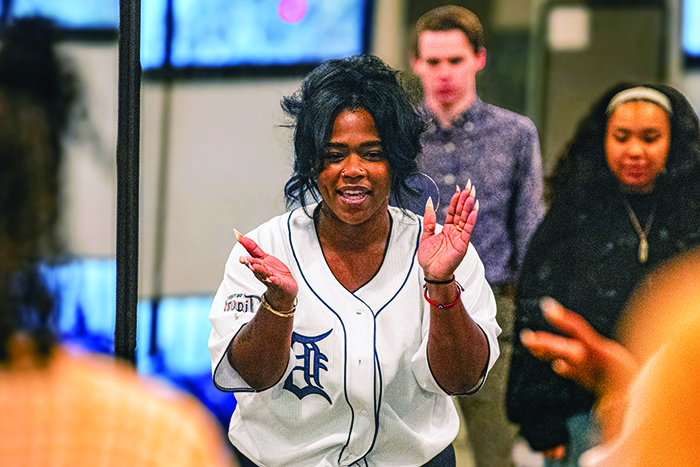

This past fall, local photographer Rayford Gray documented one of Shanzell’s workshops at the University of Michigan–Flint. The workshop was part of her role as an Artist in Residence with the University Musical Society and the University of Michigan–Flint for the 2025–2026 academic year. The residency is supported by the Theatre and Dance faculty and is connected to the university’s CASE program.

The session introduced students to tap fundamentals as a rhythmic and cultural practice shaped by history, music, and lineage. Shanzell said she approached the class in the same way the form was shared with her—through mentorship, context, and a strong emphasis on listening and musicality in relationship to the elders who practiced before her. This approach mirrors the continued growth of Mindful Movement with Shanzell, which developed out of nearly two decades of teaching in schools, community programs, and arts education spaces across Michigan.

She officially launched the initiative in 2024 to create learning environments that center cultural depth, adaptability, and access while still holding high artistic standards.

Teaching within a university setting through this residency has allowed her to bring those values into an academic space, connecting technique with historical context and investigating the work more deeply throughout the residency year.

Shanzell began dance training at the age of 5 in Flint at Creative Expressions, a community-based studio located at Berston Fieldhouse. It was one of her first points of access to dance and placed her directly within Flint’s arts community at a young age. Through that foundation, she studied with Flint tap artists as well as nationally recognized masters, including Dianne Walker, Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, and Jason Samuels Smith. Being in proximity to these artists shaped how she understands rhythm, lineage, and dance as a cultural practice—an influence that continues to guide her work today.

While tap has always been central to her practice, her training extends across multiple forms. She studied modern and contemporary dance with an emphasis on Black vernacular movement, including Dunham, Horton, Graham, and Limón techniques, along with vernacular jazz, Cecchetti ballet, and traditional West African dance. Much of this training took place during her studies at Barry University and the University at Buffalo, where working across forms helped her think more clearly about structure, musicality, and how different movement traditions speak to one another.

Practicing movement traditions connected to the African diaspora has deeply shaped how she hears music and how rhythm lives in her body. Training across these forms taught her that rhythm is something you carry—and something that gets passed on. This understanding now guides her work, especially in how she thinks about dance, community, and responsibility to the form.

No one else in Shanzell’s immediate family danced, but her movement practice is closely connected to her family’s musical lineage, particularly through the church. Her mother has mild cerebral palsy, and advocating for her access to performance spaces influenced Shanzell’s early awareness of inclusion and equity in the arts. That sense of responsibility continues to inform how she teaches and how she designs programs.

Shanzell comes from a long line of musicians. Her grandfather was the lead singer and creative force behind The Shepherds, a gospel group that traveled nationally, recorded under several labels, and later developed their own imprint, Strawberry Vinyl Records. Her uncles were self-taught guitarists, vocalists, and songwriters, and the matriarchs in her family worked as music educators.

So while no one danced, music has always been part of Shanzell’s DNA. Growing up in the church is a significant part of her musical inheritance and continues to influence how she hears rhythm, builds phrasing, and approaches tap as both a percussive and melodic form.

The way Shanzell teaches tap reflects how the form has always traveled—person to person, teacher to student, often in borrowed spaces with little more than rhythm, time, and imagination. This exchange sits at the center of Mindful Movement with Shanzell. In class, tap becomes a conversation.

“We listen closely, respond, refine our tone and sound, and learn how to sit inside the pocket together,” she said. “It’s a garden, really, and everyone tends the crop.

This past fall, local photographer Rayford Gray documented one of Shanzell Q. Page’s Mindful Movement with Shanzell workshops at the University of Michigan–Flint. The workshop was part of her role as an Artist in Residence with the University Musical Society and the University of Michigan–Flint for the 2025–2026 academic year.

“Musicality matters. Timing is important. Presence is shared. People come in with a variety of experience levels, but everyone is asked to engage fully and trust what they hear and feel in their bodies.

“There is something deeply affirming about tap dance itself,” she added. “It was birthed by our ancestors, who learned how to create joy, language, and agency out of scarcity. Doing a lot with very little is as much a part of our history as it is ingenuity—and many of us find renewed appreciation for those values, especially in times like these.”

Tap, she said, is a living practice that continues to resonate in real time, particularly within the traditions of the African diaspora. Students often realize how capable they are once they stop chasing perfection and start listening.

“What inspires me to teach is the exchange,” Shanzell said. “I feel very lucky to have this gift. Teaching keeps me in relationship with this ever-evolving tradition and with people in a way that performing alone never could. Every room is different. Every group brings its own sound, questions, and energy, and that constantly asks me to stay present and responsive.”

There’s something powerful, she said, about watching people recognize what they’re capable of once rhythm clicks and confidence follows. That moment never gets old and continues to remind her why this work matters and why it’s worth passing on.

Growing up, Shanzell watched films featuring The Nicholas Brothers, along with legends like Gregory Hines and Jimmy Slyde—history that shaped her understanding of tap dance and its connection to classic musical films and style.

“If I had to name one dancer who speaks to me most in the modern era, it would be Jason Samuels Smith,” she said. “His dancing is emotionally clear in a way that’s rare. You can hear exactly what he’s saying through his feet. His tone, phrasing, and musical choices are always intentional, and the way he listens and responds to musicians feels deeply honest.”

As a longtime student of Smith, she has witnessed his artistry not only as a performer, but also as a teacher, choreographer, and philosopher. He demands truth in movement and refuses anything less than one’s full potential—a standard rooted in lived experience and evident in everything he does.

“I also really admire tap artists like Ayodele Casel and Josette Wiggan, who pioneer their own clarity, flavor, and point of view,” she said. “That’s one of the things I love most about tap. Every dancer brings something personal, honest, and distinctly their own.”

Shanzell describes tap as a living continuum—carrying hundreds of years of expression, style, history, and community. She considers it an honor to be part of that lineage.

“Flint’s arts community has always been shaped by visionaries and sustained by generations of artists and educators who poured care into the culture,” she said. “I’m deeply grateful to those who came before me.

Their work opened pathways that allowed me to grow. My focus now is on expanding that legacy in ways that invite more people into the tradition—especially those who haven’t always seen themselves reflected in these spaces.”

The door, she emphasizes, is open. Curiosity is enough. Whether someone is new to movement or reconnecting with it, tap dance at Mindful Movement with Shanzell is meant to be a place where people can listen, move, and build their own relationship to rhythm within a supportive, community-centered environment.

To learn more, visit mindfulmovementwithshanzell.org or email Shanzell at shanzellp@gmail.com.