I’m gonna write a little letter – gonna mail it to my local DJ.

It’s a jumpin’ little record I want my jockey to play.

– Chuck Berry “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956)

From my earliest memories, I had always wanted to be “on the air.” That was all I ever had in mind. This was true even before my father died on the radio when I was six years old.

Donald J. Cavanaugh was working for the Veteran’s Administration as Chief of Rehabilitation in Syracuse by the summer of 1948. He entered WNDR’s studios to narrate a program called “News for Veterans” on Thursday morning, July 29th. It was a long, 30-minute script. Halfway through, he paused for breath. There was a problem. He slumped back in his chair. It was a massive coronary. He was dead at the age of 52, a chronological distinction I have now amazingly surpassed by two full decades.

Years later, I started riding a bike out to that same station. I was such a nuisance, they finally gave me a job answering phones on weekends for 50 cents an hour.

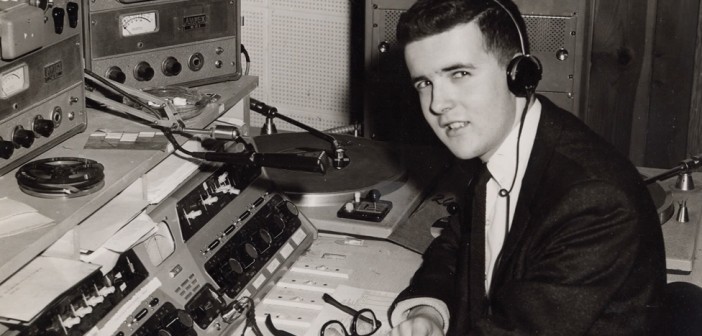

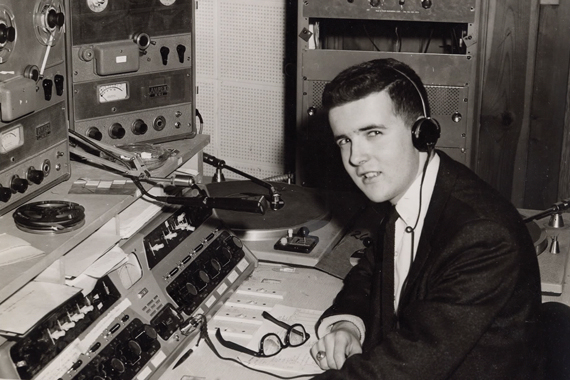

WNDR days in the late 50s marked the very birth of what we now call the “Rock Era.” It advanced in a vacuum more than partially enhanced by traditional radio professionals shunning any aspect of the new music, a fusion of grassroots “Country and Western” and black-based “Rhythm and Blues.” I and other young enthusiasts were more than willing to step forward and grab the microphones.

Soon I was doing news reports and pulling DJ shifts on weekends. During my senior high school year, I worked each night from Seven till Midnight with a 58 percent total audience share, more than every other station combined.

The last weekend of November 1963, I took it upon myself to cancel several weekend dance appearances. One of them involved an important station client, who was furious. Following a loud and fierce shouting match with our general manager, I resigned from WNDR, never to return. John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

I departed Syracuse and traveled at night through a blinding snowstorm across Southern Ontario. Crossing the Blue Water Bridge at Sarnia and entering Michigan at Port Huron, I punched on the radio and heard my own voice promoting the arrival of “Peter C. Cavanaugh at the Home of the All-American Good Guys on Big Six Hundred–WEETAC Radio–W! T! A! C!”

WTAC’s Program Director Bob Dell, an old Syracuse friend, had invited me to join him in Flint.

If WNDR was a “hot rocker,” WTAC was a power-packed blowtorch. “Big 600” was top-rated in Flint, Bay City, Saginaw, Midland and twenty surrounding counties. “PULSE” survey research showed WTAC with at least a 40 percent share of overall audience wherever its powerful signal reached – several thousand square miles.

My personal timing was impeccable. When the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, we went for it. Every other cut I played on “The Peter C. Show” was a Beatles’ hit.

In giving out “Beatles’ Books,” 10,000 of which we ordered betting on the lads, WTAC received 5,000 pieces of mail a day. A Saginaw Valley PULSE survey from April of 1964 estimated a 91 percent rating for nighttime listening on WTAC. That’s not a typo. When the first Beatles’ film, “A Hard Day’s Night,” debuted at the Palace Theater in Downtown Flint where we had set up a live remote broadcast, I was mobbed.

Then it was announced that the Beatles would appear with a four-dollar admission at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium at 2pm on the sixth of September. Utter pandemonium broke loose. But there would be no “radio interviews.”

Sure. Our mission was clear. Bob and I designed an official looking “Michigan State Police Beatle Security Pass” which we had a printer friend set to type with several colors and even the Michigan State Seal. It looked sensational.

That enchanted Sunday, we drove to Olympia and parked at the stage entrance, then casually strolled inside. We were ushered through each perimeter security point. We went right down front on the floor and, as the Beatles hit the stage, were less than 20 feet away.

They performed for no more than 25 minutes.

As captured on our cassette recorders, the entire program from start to finish was one enormous, ear-shattering, mind-rattling, caterwauling shriek as thousands of teenage girls, most barely pubescent, gave birth to the most primal roar I ever witnessed before or since.

It was beyond comprehension. And then – the moment was at hand.

Would our Beatles credentials work with their own English security squad?

“Of course, gentlemen. Right this way, please.”

We were backstage at Olympia. The Beatles were sitting at a large, uncovered banquet table. Cassette recorders in hand, we both interviewed all four. We told them who we were and how we made up the passes. We boldly asked to have our pictures taken with them, even though they knew we were uninvited intruders. The Beatles seemed to be entertained by our audacity.

Bob and I returned to Flint and spent the entire night in the studio producing “WTAC Meets The Beatles” which combined all of our floor-taping and band interviews. It became an hour-long program that reasonably captured the experience. It ran every other hour for a day and a half.

Thus began my adventures in Flint, continuing all the way through to the sale of WWCK-FM on New Year’s Eve of 1989.

The Beatles were a baptism. Imagine the exact center of your psychic universe only enticing inches away. Past commandments and catechisms, contradictions and confusions; beyond sin and salvation, you are delivered.

Unequivocal validation stretches distant into the future.

Here come Stones and Who. Zeppelin too.

Nugent and Seger.

Bare women quite eager.

Alice and KISS.

Grand Funk couldn’t miss.

Jimi needs coke.

MC5’s not a joke.

Sergeant Pepper arrives as a war shatters lives.

The power rolls in – sacramental with sin.

A life web spin.

About the Author

In 1957 at the age of 16, Peter C. Cavanaugh enjoyed a 58 percent total audience share on his hometown station, WNDR in Syracuse, NY. Decades later, he wrote “Local DJ” – a book about his adventures ever since, promoting and producing literally hundreds of early concerts with the likes of Chuck Berry, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Bob Seger, Ted Nugent, Alice Cooper, Kiss and so on, as well as running Reams Broadcasting, a seven station radio group which included the top-rated Rock & Roll stations in America. A multiple award-winning broadcast executive, Mr. Cavanaugh is featured prominently in Cleveland’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.