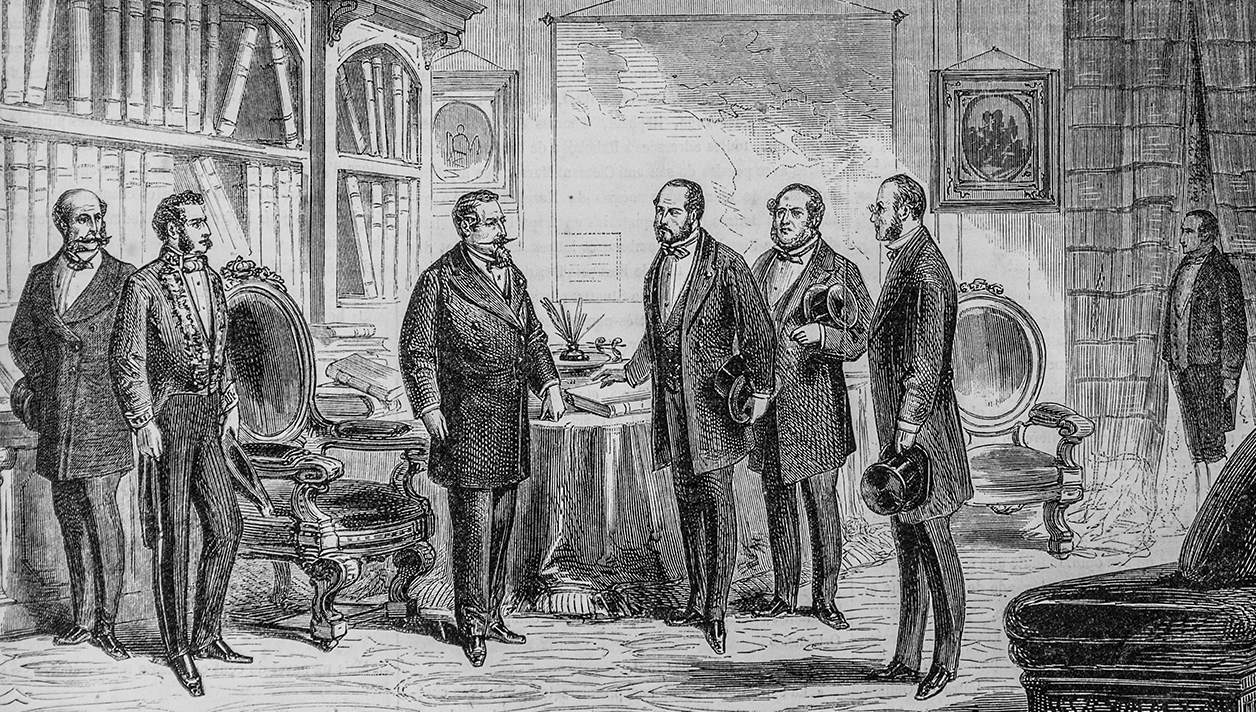

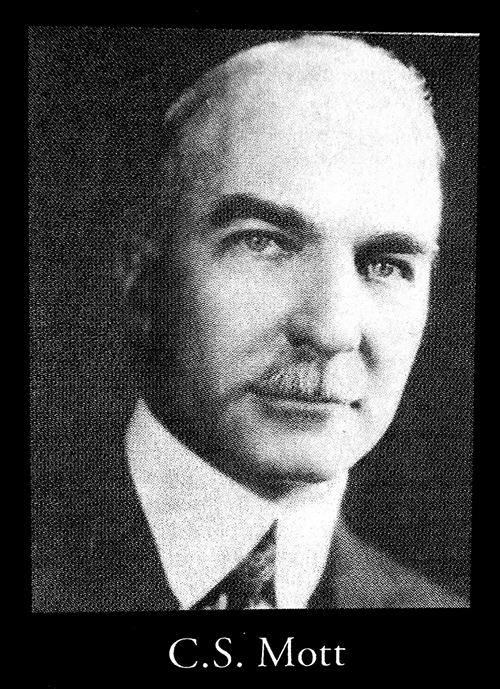

Inside the warm and welcoming, mahogany-paneled confines of the Flint Industrial Savings Bank, the dapper bank executives gathered around an impressive mahogany table. Outside, the autumn winds were blowing through that October of 1929, and soon a seismic change across America—and the world—would arrive. But inside the conference room, the executives’ designer leather shoes remained as dry as their afternoon martinis, while the smiling visage of Chairman of the Board Charles Stewart Mott looked down from a portrait hung with care.

But this was no ordinary bank meeting. This was a conclave of the “League of Gentlemen,” the ironic and secret moniker the group had chosen to identify themselves. No one outside could know—because this was no ordinary group of bankers. They were, in fact, in the midst of perpetrating the largest bank fraud the United States had ever witnessed. Together, they would steal what would be worth over $60 million in 2025 dollars.

Operating with minimal rules of engagement and tactics that would soon be deemed illegal—and usurious—in the 1930s, they took advantage of a world gripped by irrational and careless exuberance. Millions were swept up in the fever of speculation. They made easy targets. Using a range of strategies, the League had been systematically siphoning off depositors’ cash to speculate in the wild Roaring ‘20s stock market.

They leveraged the old-school “fake note from home” scheme, which required tight teamwork and skillful forgery. Another scam involved obtaining bills and drafts intended for other banks and simply filching them. They wrote IOUs in the names of local celebrities, falsely claiming those individuals owned the shares and that they were on deposit at the Flint bank. Then, they attached forged share certificates to the promissory notes. The final touch was a forged signature.

The bank would then loan money—not to the supposed shareholders, but to other “Gentlemen” in the group. They had become so brazen, they were even forging C.S. Mott’s name on documents.

Along with Mott, they forged the signature of General Motors and Chevrolet founder William C. “Billy” Durant. When they ran out of local luminaries, they expanded beyond Flint. Keeping with their automotive theme, they even faked Henry Ford’s signature. Sometimes, they simply robbed safe deposit boxes—stealing money like convenience store stick-up men, albeit in tailored suits with matching ties and shoes. They were “gentlemen,” after all.

In Flint, the League formed because they were surrounded by OPM (Other People’s Money) amid a roaring stock market. Every day in Vehicle City, more money poured into the booming auto industry. Buick, Chevrolet, AC Spark Plug, DuPont, and GM were growing by leaps and bounds.

Millionaires were minted regularly. New homes rose quickly on Circle Drive, Woodlawn Park Drive, and in the swanky new Woodcroft neighborhood off Miller Road. It seemed everyone was getting rich. The League of Gentlemen wanted their cut—and they weren’t going to wait for a promotion. No, they were just going to take it. In the most gentlemanly fashion, of course.

The Meeting

Early in October 1929, the League called a meeting at the bank, summoning each member for a private conference. Leading the meeting was Frank Montague, bank vice president. He didn’t even consider it stealing—he called it “borrowing money without approval.” Better to ask forgiveness than permission, he believed.

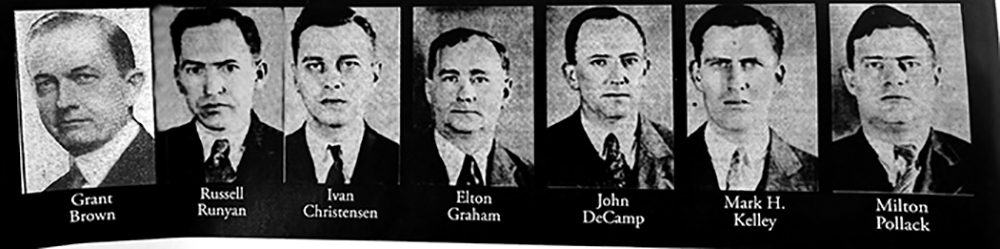

His partner in crime, Milton Pollock, a handsome 39-year-old VP on the rise, had a sick wife at home. Medical care was expensive. This seemed like a solution.

Next to them sat Ivan Christensen, the bank’s assistant cashier. He was stealing because—well—he liked money. He was building a new home in Flint for $75,000 (over $1.2 million in 2025 dollars) and was hoping no one would question how he could afford it on an assistant cashier’s salary. He’d already been at it for two years.

Settling into the rest of the cushioned seats were the other conspirators: James Barron, George Woodhouse, Russell Runyon, Clifford Plumb, Mark Kelly, David McGregor, Arthur Schlosser, Robert McDonald, Elton Graham, and Farrell Thompson.

Also present: 28-year-old Robert Brown, son of the bank’s president, Grant Brown. The elder Brown was supposedly unaware of his son’s gangster double life, and Robert Jr. intended to keep it that way. He was especially wary of getting caught. Grant Brown was a high-profile, respected figure. The Brown family was considered a “First Family” of Flint, known for their supposed moral foundation. Brown Sr. had been a bank examiner, a man who once caught embezzlers like the League of Gentlemen.

Ironically, the League only organized once its members realized they weren’t alone in their criminal activities—the bank was already full of crooks. It was like discovering your coworkers are all sports fans and athletes, but instead of forming a fantasy baseball league, they formed a larceny club. And instead of wasting time on video games or browsing the web, they focused on theft—and terrible investments.

But this was no ordinary bank meeting. This was a conclave of the “League of Gentlemen,” the ironic and secret moniker the group had chosen to identify themselves.

In Flint, the League formed because they were surrounded by OPM (Other People’s Money) amid a roaring stock market. Every day in Vehicle City, more money poured into the booming auto industry.

Bad Gamblers with Other People’s Money

One of the League’s biggest problems? They were terrible investors. Despite their insider access to OPM, their investment strategies were comically inept. But then again, it wasn’t their money.

What drove their optimism was a blind belief that the stock market would hit a new all-time high by the end of October 1929. After all, the esteemed economist Dr. Irving Fisher had recently declared that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.”

What could possibly go wrong?

The Crash

On Tuesday, October 29, 1929—everything went wrong.

An unprecedented meltdown in the overheated, unregulated, and chaotic market destroyed millions of personal fortunes—and took down the League with it.

An emergency meeting was called in the same boardroom where, just weeks earlier, they had toasted their ambitions. This time, the mood was somber.

Realizing their losses couldn’t be recouped, some members urged the group to confess. Others resisted, but under pressure—some even threatened to go public—they relented.

By the afternoon, Frank Montague calculated the group’s total losses: roughly $60 million in 2025 dollars. He had no choice but to go to Grant Brown. Together, they summoned the League back to the boardroom, where it had all begun.

One by one, they confessed—until Robert Brown Jr. entered. “You too, Robert?” his father asked. Head hung, tears streaming, the young man admitted everything.

Finally, John de Camp, Grant Brown’s right-hand man and the bank’s senior VP, arrived. Nattily dressed, with a gold banker’s pocket watch, spectacles and tie clip, he was a church deacon and socialite. His ornate home on Woodlawn Park Drive hosted Flint’s elite. Brown Sr. stared a hole through him.

Then he picked up the phone and called Mott.

Reckoning

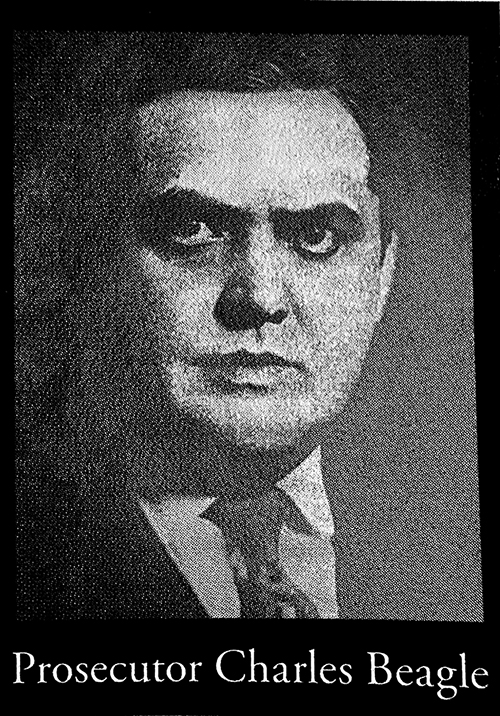

Mott rushed to Flint to assess the damage. He immediately demanded the resignation of every man involved, then called Genesee County Prosecutor Charles Beagle.

According to The Day the Bubble Burst by Max Morgan-Witts and Gordon Thomas, Beagle’s son John believed Mott asked his father not to prosecute, to avoid a public scandal. Beagle refused.

Conversely, Mott’s son, Harding Mott, insisted that no such request was ever made.

Regardless, Mott acted swiftly. In a move straight out of a Hollywood film, he withdrew $60 million (in today’s dollars) from his personal accounts in Detroit, led a three-car armored convoy to Flint, and physically replaced the stolen funds in the bank.

There was no FDIC insurance at the time. Mott’s gesture was extraordinary. He did it without a written agreement, unsure if he’d ever be paid back.

Meanwhile, Prosecutor Beagle moved forward. On November 16, 1929, warrants were issued and arrests made.

Those who pleaded guilty included Graham, Montague, Pollock, Christensen, Runyon, Kelly, Barron, and Plumb. Brown Jr., Thompson, Woodhouse, and McGregor stood trial.

In a twist, Grant Brown was charged with embezzlement and falsifying bank statements. Whether he was part of the League remains unclear—but at the very least, he was asleep at the wheel.

By January 1930, sentences were handed down:

- Graham, Pollock, Kelly, and Runyon: 5 to 20 years

- de Camp: 10 to 20 years

- Christensen: 7 to 20 years

- Montague: 3.5 to 20 years

- McDonald, Brown Jr., and Plumb: 6 months to 20 years

An editorial in Flint Saturday Night summed it up: “Ali Baba and his forty thieves were the mildest sort of lambs compared with the contemptible dirty dozen who pilfered and robbed this bank … Grant J. Brown was its president … A wizard he surely was—either a fool or a knave to have permitted such a state of affairs.”

Postscript

While in prison, the League of Gentlemen were allowed adjoining cells. In a scene straight out of “The Shawshank Redemption,” they worked together to straighten out the prison’s financial records.

Later, seven members returned to Flint—and quietly worked until retirement … in local banks.