December, 1941: Louise Bernhardt (now Kinsman) lived in a cottage approximately 50 feet from Battleship Row, Pearl Harbor, HI. She was the daughter of Chief Petty Officer F.D. Bernhardt, Leading Chief of Operations at Ford Island and on December 7, she was eyewitness to the day which will forever live in infamy. Today, 73 years later, Louise still remembers it clearly.

December, 1941: Louise Bernhardt (now Kinsman) lived in a cottage approximately 50 feet from Battleship Row, Pearl Harbor, HI. She was the daughter of Chief Petty Officer F.D. Bernhardt, Leading Chief of Operations at Ford Island and on December 7, she was eyewitness to the day which will forever live in infamy. Today, 73 years later, Louise still remembers it clearly.

“Being a Navy brat, I got used to moving around with my family a lot,” the 89-year-old says of her youth. “I attended ten different schools in 12 years and by the time we were stationed at Ford Island when I was 15, I’d learned to smile and make friends quickly.” Although Ford Island offered many amenities, there was no school, so every weekday, Louise walked to the motor launches to get a ride across the harbor to the High Navy Yard, where a bus waited to take her to high school. “Our house was at the end of the cul-de-sac, right next to the water,” Louise explained, “and as tensions rose with Japan, more and more ships docked outside our house until it became known as Battleship Row. I remember, the night before the attack, my mother commented to my dad how beautiful the ships looked in the moonlight, and how many of them there were. My dad said, ‘Uncle Sam’s letting the sailors get their Christmas shopping done.’”

The official casualty count from the attack on Pearl Harbor wasn’t released until 1962: 3,581 people.

“It was about five minutes to eight o’clock when the raid started,” Louise recalls of the day which will live in infamy. “I was getting ready for Sunday school and I heard a rumbling. My first thought was, Why are they dredging the canal on Sunday?” The harbor’s shallow water had necessitated dredging, and this was significant because the shallow depth had given the Navy a false sense of security, since they mistakenly believed that the Japanese did not possess torpedoes that were effective in shallow water. “My mother ran in and told me to get dressed because we were being attacked,” she continued, “My dad had told her that we had to get away from the house before the ships blew up.” The Petty Officer’s fear was realized less than ten minutes later, when a torpedo struck a million pounds of gunpowder in the USS Arizona’s forward magazine and exploded, killing 1,177 men.

Louise says that when she and her family stepped out of their house, the scene was terrifying. “The USS Oklahoma had been hit and was already listing, taking on water which would eventually capsize her,” she remembers. As they stood there, another moment both terrifying and surreal was indelibly etched into memory. “The Japanese bombers were flying low,” Louise said, “and one plane passed so close to us that we saw the pilot in the cockpit. His canopy was open and he smiled at us as he flew by.” The family made it to the administration building, but not without considerable difficulty. Once there, her dad went to his station while the women and children were sent to a shelter. Louise assisted in coordinating the move. While on route, they passed by her house, which was now engulfed in smoke and flame from the Arizona’s explosion. “Even the water was on fire,” she recalled, explaining how the fuel leaking from the damaged ships floated on the water, creating a fiery death trap for sailors who abandoned ship.

A long and sleepless night of terror passed in the Bachelor Officers Quarters, and in the morning, the Bernhardt family returned to the chaos that was once their home. “Shrapnel was everywhere: it had penetrated the walls, and even shredded the clothes in the dresser drawers,” Louise remembers. The family stayed in the house until after Christmas, living each day according to orders handed down from the top. “Everything had stopped,” she recalls, “and the schools were closed. We just waited.” They waited for a month, until on December 30, Louise, her mother and sister were evacuated by cruise ship to California, while her father stayed behind to man his post for the next 26 months. Every night until Christmas Eve, as Louise lay in her bed, she could hear a tapping sound coming from one of the ships just outside. When she asked her father about it, he told her it was probably a battery that needed replacing. It wasn’t until Louise moved into Abbey Park, the Grand Blanc retirement community where she now lives, that she discovered the truth. “The tapping sound had come from men trapped in the submerged hold of the USS West Virginia,” she said crying. “They banged on the walls of the storeroom for 16 days before they finally died.” Rescue for those men had been impossible; in fact, many sailors were drowned during previous rescue attempts on other ships.

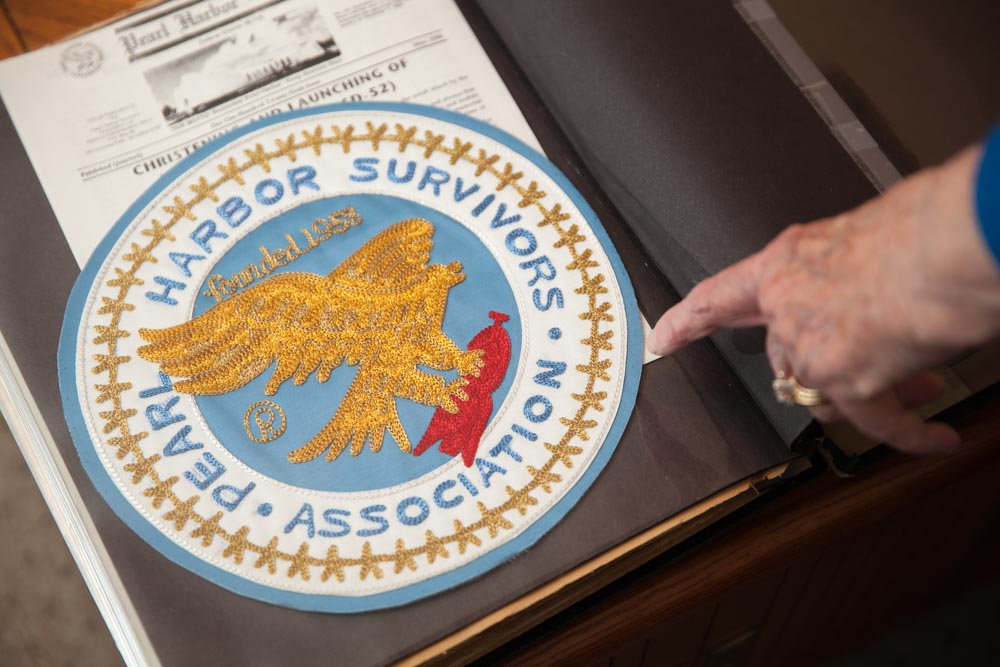

It’s been 73 years since the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Louise says that her memories are as close as ever. All these decades later, the attack remains a subject of engrossing interest to her. Louise’s apartment is filled with books and articles on the topic, and she has personally connected with many other survivors through commemorative events and news articles. Her passion is driven by her memories. “A lot of survivors did heroic things that day, and I will always remember and honor those people,” she said. ♦

Photography by Mike Naddeo