In the early 1950s, war again populated the headlines. The Red Scare was the social phenomenon of the day and when communist-backed North Korea invaded South Korea in June of 1950, the U.S. leapt back into war. The resulting Korean War would last for three years and cost the lives of over 36,000 United States Soldiers and over 1.5 million Korean civilians. Back home, hints of corruption in the Truman camp and the fighting in the Korean war convinced the President to not seek office a third time. In 1952, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme allied commander of European forces in WW2, defeated Adlai Stevenson for the presidency in a landslide. Eisenhower would defeat Stevenson again in 1956, in the same fashion.

The latter half of the decade was dominated by the African-American push for Civil Rights. What started as a whisper in the late 1940s was heard by all in 1954 after the landmark Brown Vs. Board of Education decision. In 1955, Rosa Parks stood up to racist policy, kicking off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. President Eisenhower then signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, protecting the right to vote. The act was a small victory for minority activists and would not be the last. Afterward, Martin Luther King Jr. met with prominent African-American leaders in order to coordinate the non-violent and peaceful protests that would quickly change the face of the nation.

The 1950s also provided color television, the rise of the suburbs, rock and roll music and two more States – Alaska and Hawaii.

For the City of Flint, the 1950s started with tragedy and ended in celebration. The population was continuing to grow and with this growth came a renewed interest in education and culture. The city was also gaining a nationwide reputation for a reliable sense of hard work, staunch determination and a resolute community. Welcome to Flint in the 1950s.

1950-54

The Storm of the Century

In 1943, during the war effort, the Flint community came together to raise $1 million to establish a new and larger facility for the then women’s hospital located on Lapeer Street. After the war, the community raised another million dollars for the hospital and in October 1951, the new McLaren General Hospital opened on Ballenger Hwy. The hospital was named after nurse Margaret E. McLaren – the superintendent of the previous women’s hospital.

Also in early 1951, Freeman Elementary school opened as the first community education school in the city, under the direction of the first community school director, William F. Minardo. The school was named after Ralph M. Freeman, a prominent city attorney and prominent school board member. In 1954, President Eisenhower appointed Freeman Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court.

The Flint crowds could hardly contain their enthusiasm when Dwight D. Eisenhower visited Flint on the campaign trail in 1952. Not to be outdone, Adlai Stevenson held a rally in the city on Labor Day. Flint directly affected the Eisenhower campaign in the person of Arthur E. Summerfield, owner of one of Michigan’s largest GM dealerships. He used his success to gain influence in the Republican Party and in 1952 was elected national chairman. He was a major influence on the Michigan delegates and could be credited with saving the political career of Richard M. Nixon who, at the time of the ’52 election, was surrounded by scandal. Eisenhower wanted to dump Nixon as his running mate but Summerfield refused, stating that he would not call another convention. After his inauguration, President Eisenhower named Summerfield Postmaster General, where he served from 1953-61.

It Struck without Warning

June 8, 1953 started as a breezy, humid day and grew into a blustery afternoon. The forecast for that evening called for thunderstorms with potentially strong winds and hail. For those living on Coldwater Rd. in Beecher, just north of the Flint boundary proper, the day seemed ordinary. School had just let out for the summer. Kids were playing. Mothers were hanging laundry out to dry and fathers were driving home from a busy day at GM. Around 8pm, the sky turned the black-green-yellow color of an old bruise. Lightning blitzed the sky. Soon, a dark chimney-shaped cloud formed above Coldwater Road, just west of Linden Road. A sound like a freight train filled the air. The Beecher Tornado formed in an instant and in less than an hour, changed the lives of those in its path and all who knew them.

The Beecher Tornado ranks in the top ten of our nation’s deadliest storms. To date, it is the only F5 intensity tornado to ever touch down in Michigan. With winds gusting to over 200 mph, the 800-yard wide tornado left a 27-mile path of destruction. It caused over $16 million in damage ($150 million in 2019 value), which included 600 homes, Beecher High School, and other farms and businesses. It is regarded as the worst natural disaster in state history. Immediately after the storm passed, the communities of Flint and Genesee County sprung into action. People arrived to provide as much help as they could. Families took in survivors and children who had lost parents. Neighbors transported the injured to hospitals. With so many dead, the National Guard Building was used as a temporary morgue. State Troopers, the National Guard and the Red Cross were on the scene. Local doctors donated their services and worked around the clock. The tragedy touched everyone. At the end of it all, 116 people were dead with over 800 injured. Twenty families reported multiple deaths with the Gensel and Gatica families losing five members each. For many people, life was forever changed. It was then that Greater Flint taught the nation a lesson in compassion and community. Immediately after the night ended, a “red feather” campaign was launched to help raise funds to rebuild. In late summer, one of the nation’s biggest ever “Builder Bees” was held, bringing the entire community together to rebuild. Greater Flint will always stand up for its own and lend a hand to those in need.

The year 1954 provided a fresh set of opportunities for those who dreamt of making an impact and Michael Gorman, then editor of The Flint Journal, had an idea. He believed that Flint needed more educational and cultural resources. He expressed his ideas to the Calumet Club, an informal group of fellows who gathered at his home to play cards. The initial idea was for private contributions of $25,000 or more to be used to build an art center, planetarium, historical museum and theater. The Club became the Committee of Sponsors for the Flint College and Cultural Development. The goal of the committee was to raise $25 million for the project. GM contributed $3 million in starter funds and over 400 individuals and corporations donated. The Flint Cultural Center was born.

In the summer of 1954, GM debuted its 50 millionth car in a parade down Saginaw to much fanfare. The parade was quite the spectacle as gawkers came from miles around to get a look at the vehicle. The special car was revealed to be a gold-plated Chevy Bel Air Sport Coupe. It was one of a kind. The car would move into private ownership after its days as a spokesmodel for GM were done, and has since disappeared.

1955-59

It’s a Celebration!

In 1955, Flint began a five-year stretch of growth and celebration. First, a new campus for the Flint Junior College would open on 32 acres of land donated by Applewood Estate and Charles Stewart Mott. The first building to be built was Ballenger Field House, named for Buick Co-founder, William S. Ballenger.

Immediately after the new Flint Junior College opened its doors, a groundbreaking ceremony was held for the University of Michigan-Flint Branch. C.S. Mott and U of M President, Harlan Hatcher, tossed the first shovels of dirt. Classes for the new University branch began a year later, held on the Flint Junior College campus until the first UM-Flint building was completed in 1957.

The summer of ’55 marked the city’s centennial and Flint held a grandiose celebration. The great Centennial Parade pulled in a crowd of over 200,000 persons as it made its way down Saginaw. After the parade, the crowds flocked to the Flintorama Pageant at Atwood Stadium. The pageant entertained the populace for hours as it told the story of Flint’s 100-year history. Special guest, Dinah Shore, was on hand to electrify the crowd. The festivities ended with a dedication of Flint’s new Municipal Center, courtesy of Richard M. Nixon. The Flint Municipal Center included the City Hall, police headquarters, fire headquarters and a small, domed auditorium. Nancy Kovacs was chosen “Miss Flint” and would go on to star in many Hollywood films.

That year also marked advancements in Civil Rights when WAMM-AM became the city’s first radio station to offer programming dedicated to African-Americans. One of the first deejays was the legendary Casey Kasem. The radio station is now WFLT 1420 AM. Herman Gibson, the head of the Flint NAACP, started The Bronze Reporter, a newspaper dedicated to providing news of the Civil Rights movement to the area’s African-American citizens.

The party wagon kept right on rolling, culminating in 1958, when GM held its 50th Anniversary Celebration in the city. It was a raucous year and GM spared no expense. The festivities started early. In November of 1957, the company aired a two-hour television special, “The General Motors Fiftieth Anniversary Show.” It was watched by over 60 million people and the highlight was Helen Hayes’ recital of “The White Magnolia Tree.” The star-studded feature included Eddie Bracken, Don Ameche, June Allyson and Claudia Crawford. Next, GM opened their plants to everyone for guided tours, and millions lined up around the country.

Locally, GM formed the Flint Citizens Golden Milestone Committee to coordinate activities for the occasion. “The Golden Dress-up,” a city-beautification campaign, proved very successful as the entire city pitched in leading up to the massive Golden Milestone parade, attended by residents of Flint and beyond. More than 20 bands from different colleges around the nation marched down Saginaw, followed by fantastic floats displaying GM cars from every decade. One float held an ice-skating rink where Olympic Figure Skating Champion, Tenley Albright, flashed her skills. One float held celebrity Pat Boone, and the Durant Hotel was besieged by teenage girls when the city learned where he was staying. Zorro, played by Guy Williams, was a big hit with kids lining the parade route. Local AC Delco employee, Sophia Branoff, was named “Golden Milestone Girl.”

While the GM festivities were in full flux, the Flint Cultural Center was beginning to form. In 1958, the DeWaters Art Center was the first building constructed in the Kearsley Street area. It was fully funded by a gift of $1,362,000 from Enos and Sarah DeWaters. The Flint Institute of Arts moved in upon its completion. In 1959, a large quantity of French and Italian Renaissance art was donated and an addition was built. Construction was also completed on the Planetarium and Bower Theater. Programs began immediately and an addition was made to the Planetarium in 1959. Higher learning in Flint was enhanced in ‘58 when the Flint Public Library was completed in its current location on the Cultural Center campus. The summer also saw the city’s first Civil Rights protest at the new Flint City Hall.

The last major opening celebration came in 1959, when Flint Southwestern High School was opened for students, taking the place of Flint Technical.

The 1950s were a banner decade for prosperity in Flint. It proved that Flint was one of the most resilient and compassionate cities in the world. The advancements in culture, education and Civil Rights would continue for Flint through most of the sixties, without a trace of worry for what the future would hold.

Rocket Mail!

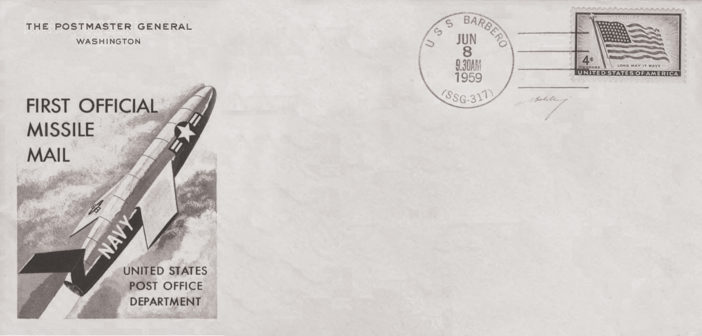

During Summerfield’s tenure as Postmaster General, the image of the post office was upgraded to reflect the new era. The color scheme was re-imagined to the red, white and blue we recognize today and leaps were made in mail efficiency. Summerfield issued an increase in postal rates to raise money for mechanical innovations. In order to advertise the postal service, he started a television show entitled, “The Mail Story: Handle with Care.” The show ran for three months in 1954.

In his enthusiasm to increase efficiency even more, Summerfield experimented with rocket-delivered mail. In 1959, a regulus cruise missile was launched from the U.S. Navy submarine USS Barbero onto mainland United States. It was filled with commemorative postcards addressed to President Eisenhower and members of the Universal Postal Union. The missile landed successfully at Naval Station Mayport in Florida. It was opened and the mail was forwarded to the Jacksonville, Florida post office for routing. Summerfield claimed it an immediate success stating that the event was, “of historic significance to the people of the entire world.” He went on to predict that, “before man reaches the moon, mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to Britain, to India or Australia by guided missiles. We stand on the threshold of rocket mail.” This, for obvious reasons, never came to be.

Other Notable Events Timeline

1951

- Dr. Raymond Gerkowski became director of the Flint Symphony Orchestra.

1953

- GM produced the first Chevrolet Corvette.

- Flint’s first television station, WTAC-TV, began broadcasting.

- David Hoskins became the first black Flint native to play in the Major Leagues (Cleveland Indians).

1954

- Boxer Jimmy Carter was the first black guest at the Durant Hotel.

1955

- George R. Friley became the first black chairman of the County Board of Supervisors.

1958

- Durant-Tuuri-Mott Elementary School was rededicated.

- Flint hosted the National Science Fair.

- The Buick Open was played for the first time.

- The first Flint CANUSA games were held.

- WJRT-TV studio began programming.

References

Azizian, C. (2008). Community supporters made flint cultural center a reality. Mlive.com. Retrieved from mlive.com/flintjournal/business/2008/07/community_supporters_made_flin.html

Harrison, J. (2018). June 8, 1953: Flint tornado kills 116. MSU.edu. Retrieved from blogpublic.lib.msu.edu/red-tape/2018/jun/june-8-1953-flint-tornado-kills-116/

Lawlor, J. (2008). In flint, Bronze Reporter kept blacks informed…Mlive.com. Retrieved from blog.mlive.com/flintjournal/newsnow/2008/02/in_flint_bronze_reporter_kept_1.html

McLaren Health Care. (2019). History. Mclaren.org. Retrieved frommclaren.org/main/mclaren-history.aspx

Mott Community College. (2019). A brief history of MCC. Mcc.edu. Retrieved from mcc.edu/about/about_history.shtml

National Weather Service. (1970). The science behind the Flint-Beecher tornado. Weather.gov. Retrieved from weather.gov/dtx/beechermet

Public Relations Staff. (1958). Our 50th Year. Detroit, MI: General Motors

The Flint Club. (2006). Timeline of Flint. Flinthistory.com. Retrieved from: archive.li/jzTLw