The scene was chaos. Police officers fired bullets and tear gas into the crowd of picketers and at the band of strikers at the gate to Fisher Body #2. Picketers and strikers retaliated by throwing rocks, bolts, door hinges and screws. A police car was flipped and the violence was escalating. Victor Reuther maneuvered the sound car (a car with a PA system mounted on the top) slowly through the crowd while shouting encouragement for strikers through a bullhorn. Sitting to his right, Genora Johnson saw an opportunity to protect the workers from police, show solidarity and calm the night. Taking the bullhorn from Reuther, she rallied the women on the street to break through the line of cops and defend their husbands, brothers and friends shouting, “we will form a line around the men, and if the police want to fire then they’ll just have to fire into us!” Women bravely heeded her call and moved to stand in the way of the cops and their weapons. The wall of women was unbreakable with cops unwilling to advance with force against it. The Battle of the Running Bulls was over, but the work of the Women’s Emergency Brigade had just begun.

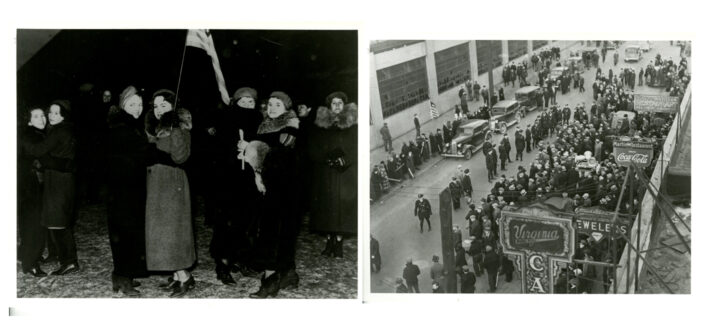

The Women’s Emergency Brigade was started by Genora Johnson-Dollinger as a militant expansion of the UAW’s Women’s Auxiliary with the purpose of supporting and protecting the UAW strikers through any means necessary. Brash and courageous, the women faced down guns, goons, sexism and hate. By no means cheerleaders, the brigade played a pivotal role in the fight to win worker’s rights and in the establishment of the United Auto Workers (UAW).

The Women’s Emergency Brigade was started by Genora Johnson-Dollinger as a militant expansion of the UAW’s Women’s Auxiliary with the purpose of supporting and protecting the UAW strikers through any means necessary. Brash and courageous, the women faced down guns, goons, sexism and hate. By no means cheerleaders, the brigade played a pivotal role in the fight to win worker’s rights and in the establishment of the United Auto Workers (UAW).

Heading into the winter of 1936, the relationship between General Motors and its blue-collar employees was at its breaking point. The past summer was a tragic one for workers. Temperatures inside the plants soared to over 100 degrees and workers passing out on the line was commonplace but never addressed. Factory foremen verbally (and sometimes physically) abused workers routinely and without accountability. Pay was cut and production was increased. Women workers dealt with it all and more as their pay averaged a quarter of the men’s and sexual harassment was occurring daily. Workers had no real way to fight back. The country was in the middle of the Great Depression and they couldn’t afford to be fired. GM held all of the power.

Things seemed bleak for workers and finding opportunity, the fledgling UAW began to secretly make headway into the plants. Led by the Reuther brothers, secret meetings were held in basements throughout the city. Genora Johnson and her husband, Kermit, were regular meeting attendees.

Johnson was always a firm believer in worker’s rights. A self-proclaimed socialist, she was extremely adept at organizing for a cause. She formed the Flint Chapter of the Socialist Party of America and, before the sit-down strike, organized a group of high-schoolers to deliver pamphlets to auto workers throughout Flint. She made her office in the Pengelly building (current home of Ennis Center for Children) and offered space to the Reuther brothers and the UAW. It became strike headquarters.

When the sit-down strike abruptly began in December 1936, the city was divided; it was labor vs management. Could the workers take on the giant that was GM and win? Workers from all over the state rallied to the cause. On New Year’s Eve, a large celebration was held on the street in front of Fisher Body #2 in support of the strikers. Genora Johnson was in attendance and witnessed workers’ wives and sisters shouting for their men to leave the plant immediately. Some even threatened divorce. Johnson realized that if the strike was to be successful, women had to play a major role. That night, she formed the Women’s Auxiliary.

The Flint Women’s Auxiliary was unique; created to support the UAW and auto workers, it existed as a separate organization. The men of the UAW had no input in its actions (although that didn’t stop them from trying). In the past, ladies’ auxiliaries generally supported organizations through fundraisers, cooking, or “box lunch” giveaways – women were treated as nothing more than trophies to be won. Johnson resisted any relegation to the sidelines. In fact, when it was suggested that she help by working in the kitchen, she replied, “You’ve got a lot of skinny men that aren’t capable of going out and standing or marching around the picket lines, and they can peel potatoes as well as we can.” The Women’s Auxiliary instead took an active role in all aspects of the strike. They fed strikers, ran first aid, staffed picket lines and a daycare center, and readied women for leadership roles through education on concepts such as labor history, public speaking, politics and political organizing. Immediately, GM started a misinformation campaign against them, likening them to common streetwalkers hired by the UAW to service strikers. In response, the Women’s Auxiliary sent older members to the homes of strikers to explain to the wives and families what they were truly about and to recruit participation.

The Women’s Auxiliary was changed substantially by the Battle of the Running Bulls. When Genora Johnson took the reins from Victor Reuther in the car that night, it was the beginning of the end for GM. Women demonstrated their power by holding the police and company goons at bay. Afterward, Johnson formed a more militant arm of the Auxiliary and dubbed it the Emergency Women’s Brigade (EB). The women used military titles (with Johnson as captain and a number of lieutenants) and wore colored berets and armbands for identification. Emergency brigades were organized in other cities around the state, each with a different beret and armband color designation. The color for Flint was red, Detroit was green, Lansing white and Pontiac, orange. The GM puppet Flint Journal immediately branded the Flint EB as communist due to their choice of red as a designated color. This did not hamper their efforts one bit. Notable EB lieutenants included Teter Walker, Ruth Pitts and Nellie Besson.

The EB started with a membership of 50 but quickly expanded to 350, and because they were risking their lives, a member of the EB had to possess specific qualities. Membership was available to “women who could be ready in a moment’s notice, and who could stand the sight of blood without falling to pieces.” The EB held the line between the police and the strikers daily. They brandished a variety of “heavy clubs” (as one newspaper put it) their weapons consisting of rolling pins, boards, whips and bats, among others. When workers were being gassed in the factories, the EB used their weapons to break out windows and allow the gas to dissipate.

Perhaps the EB’s biggest moment came during the UAW takeover of Chevy #4. The UAW knew that if they were to take control of that plant, they would have GM on its knees. Chevy #4 was responsible for the Chevy engines and a main production cog. The UAW created a plan that featured the EB as a major force. Due to known informants in their midst, the UAW released a plan to take control of Chevy #9. GM moved to block and oust UAW members from that plant, leaving Chevy #4 for the taking. Under the leadership of Kermit Johnson, the UAW infiltrated #4 and began taking control. Meanwhile, the EB blocked the main gate, forming a human chain and barring goons, police or National Guard until the UAW had control inside. The takeover was successful and, with Chevy #4 in the hands of the UAW, GM had nothing left but to capitulate to most union demands. The sit-down strike lasted 44 days and ended on February 4, 1937, catapulting the UAW into the national scene and almost single-handedly creating the country’s middle class. It all may not have happened if it weren’t for the Emergency Brigade and Women’s Auxiliary.

After the strike, the EB disbanded. Genora Johnson moved on to Detroit where she remained politically active for the rest of her life. In history books and writings, many have tried to relegate EB to nothing more than cheerleaders, including the male leadership of the UAW. What the women of the Auxiliary and the EB did was turn the tide of the strike in favor of the union through sheer guts and confidence. The EB also instilled hope and the fight for women’s rights in its members, with one member stating that the women of the EB have a “completeness about them, the satisfaction and wholeness that people have when they are using all their powers instead of letting four-fifths of their potentialities rot unused as in the case with so many women who life makes only the demand to live like a lady.”

“We weren’t a tea-drinking society,” said Genora Johnson-Dollinger when asked about the militant mindset of the women in the EB. The EB and Women’s Auxiliary played a role equal to that of the men of the UAW and should not go unrecognized. They were soldiers in their own right, dedicated to equality and support of the biggest labor movement of the 20th century.

References

Photos Provided by Genesee Historical Collections Center – University of Michigan-Flint & LOC.gov

Encyclopedia.com. (2021). Women’s emergency brigade. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved from encyclopedia.com/economics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/womens-emergency-brigade

Genesee County Historical Society. (2021). Genora Johnson-Dollinger. Geneseehistory.org. Retrieved from geneseehistory.org/genora-johnson.html

Marquis, E. (2019). Women that would gladly give their life…Jalopnik.com. Retrieved from jalopnik.com/women-that-would-gladly-give-their-life-how-the-para-1838948989

Workman, A. and Hasset, J. (1994). Never again just a woman. The American Socialist. Retrieved from marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/amersocialist/neveragain.html.