Between the years 1638 and 1640, a fierce battle ensued in and around Genesee County. From the north, the Native American Chippewa Tribe (with the help of the Ottawa Tribe) attacked the Sauk Tribe. Merciless and well-orchestrated, the attack left no Sauk dwelling unturned. The bloody battle resulted in the complete expulsion of the Sauk tribe from the area and the entire State of Michigan. The Sauk were forced to migrate west, finally taking up a permanent position on the banks of Lake Michigan, in the current-day State of Wisconsin. Many Genesee County residents have heard the story of the Battle of the Flint River. Is there truth to it … or is it simply a legend?

In approximately 1600 (the exact date is not known), the Sauk Tribe traveled to the Saginaw Bay area from the St. Lawrence river region in the State of New York. It was believed that the Sauk were forced out of their former home by the larger and more powerful Iroquois. The Sauk then settled in the area between current-day Bay City and Detroit. Some believe the name “Saginaw” is derived from the Chippewa word meaning “where the Sauk were,” originating from Sak-e-nong or “Sauk Town.” Other reports agree that Saginaw is named for its Sauk inhabitants, but instead claim that the name comes from the Ottawa Indian word “Swageh-o-no” meaning “the-people-who-went-out-of-the-land” – a title given to the Sauk when they moved to the area from the St. Lawrence River. For many years, the Sauk prospered in the rich lands of the Saginaw Valley where the ground was fertile and game was plentiful.

The Chippewa (or Ojibwe) Tribe inhabited the lands north of the Saginaw Bay in 1600. Farming and hunting proved much harder in their lands than those of the Sauk due to the harsher northern climate. It is, perhaps, worth noting that the Chippewa were allies of the French settlers and fought with the French against the British in the Indian War. Some believe that it was the French who orchestrated the Chippewa attack on the Sauk and armed them in order to obtain Sauk lands for the enrichment of the fur trade. This seems far-fetched, since many believe the Battle of the Flint River to have occurred between the years 1638 and 1640, whereas the first French visit to Michigan’s Lower Peninsula is believed to have happened in 1669, when Adrian Jolliet and Jean Pere traveled down the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers in search of new grounds for the fur trade. (In fact, historians believe that the French did not encounter the Sauk Tribe until 1667 in the current State of Wisconsin).

Sometime in years 1638-40, the Chippewa turned their eyes on the land of the Sauk. After forming an alliance with the Ottawa Tribe residing, at the time, in the lands South of the Sauk territory (present-day Detroit), they sprung a surprise attack that completely fooled and decimated the Sauk. What follows is from The History of Genesee County, Michigan by Everett and Abbotts, published in 1879:

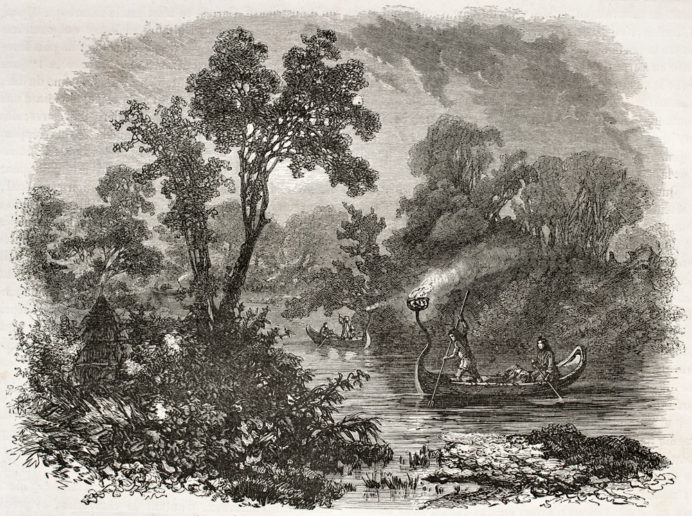

The invaders entered the country of the doomed tribes in two columns – one, composed of the southern Ottawa, coming through the woods from the direction of Detroit, and the other, made up of the Chippewa, setting out in canoes from Mackinaw, proceeding down along the western shores of Lake Huron and the bay of Saginaw, paddling by night, and lying concealed in the woods by day. When the canoe fleet reached a point a few miles above the mouth of Saginaw River, half the force was landed; and the remainder, boldly striking across the bay in the night-time, disembarked at a place about the same distance below the mouth of the Saginaw. Then, in darkness and stealth, the two detachments glided up through the woods on both sides of the river, and fell upon the unsuspecting Sauk like panthers upon their prey. The principal village – situated on the west side of the river – was first attacked; many of its people were put to the tomahawk, and the remainder were driven across the river to another of their villages, which stood on the eastern bank. Here they encountered the body of warriors who had moved up on that side of the river, and a desperate fight ensued, in which the Sauk were again routed, with great loss. The survivors fled to a small island in the Saginaw, where they believed themselves safe, at least for the time, for their enemies had no canoes in the river. But here again they had deluded themselves, for in the following night ice was formed of sufficient strength to enable the victorious Chippewa to cross to the island. This opportunity they were not slow to avail themselves of, and then followed another massacre, in which, as one account says, the males were killed, to the last man, and only twelve women were spared out of all who fled there for safety. So thickly was the place strewn with bones and skulls of the massacred Sauk, that it became known as Skull Island.

After completing their bloody work on the Saginaw, the invading army was divided into detachments, which severally proceeded to carry destruction to the villages on the Shiawassee, Tittabawassee, Cass, and Flint Rivers. Meanwhile, the co-operating forces of Ottawa, coming in from the south, struck the Flint River near its southern-most bend, and a desperate battle was fought between them and the Sauk, upon the bluff bank of the river, about a half-mile below the present city of Flint. Here the Sauk suffered a severe defeat, and retreated down the river to a point about one mile above where the village of Flushing now is; and there another battle was fought, as bloody and disastrous as the first. Still another deadly struggle took place on the Flint, a little north of the present boundary between Genesee and Saginaw Counties; and on this field, as on the others, the bones of the slain were found many years afterwards. Equally murderous work was done by the bands which scoured the valleys of the Shiawassee and the Cass, and everywhere the result was the same – the utter rout and overthrow of the Sauk.

The battle account provided by the authors is gripping, but quite sensationalized. It makes for a good read, but its specificity brings about speculation as to its authenticity. This account comes from one Ephraim S. Williams – a land merchant of some renown amongst people of Genesee County during the late 1800s. (Interestingly enough, Ephraim S. Williams was the seventh mayor of the City of Flint. His tenure only lasted a year, from 1861-62.) Ephraim S. Williams has also claimed to have seen the skulls, as they were excavated from “Skull Island.”

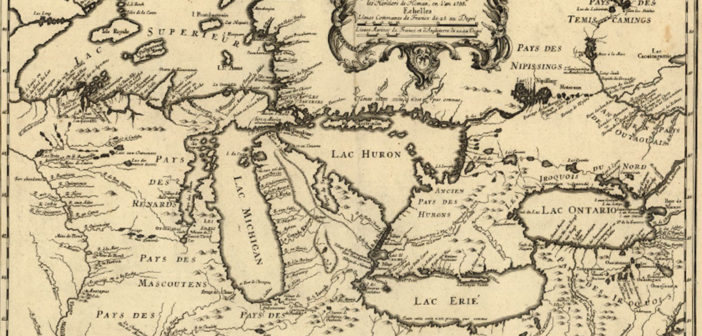

There is some belief that the entire battle is a work of fiction, with some even claiming that the Sauk were never in Michigan to begin with. The claim is based upon the idea that French explorer Samuel De Champlain mistakenly wrote that the lands of the Sauk Nation existed West of Lake Huron, instead of Lake Michigan as he was told by natives. This error was copied throughout the French maps of the day and therefore, the error persisted throughout the centuries. If this was true, then how do we have the name “Saginaw”? or knowledge of the Sauk Trail (an early Native-American trail running through Illinois, Indiana and Michigan)? The idea that a clerical error could lead to an in-depth history of an entire people seems far-fetched.

Still others believe that the story was created by the Chippewa themselves as a way to give glory to their ancestors. However, evidence of the truth of the battle account is vast and far more convincing.

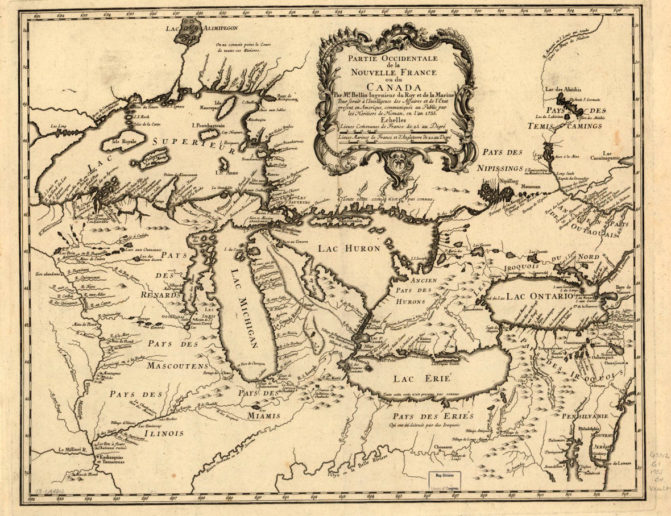

Bellin, Jacques Nicolas, and Homann Erben. Partie occidentale de la Nouvelle France ou du Canada. [Nürnberg, 1755] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/73694802/>.

As for the Battles in Flint and Flushing mentioned in the prior account, physical evidence exists.

In Flushing, arrowheads and other Native American artifacts have been found in and around the area of Mill Street and in 2008, during a building project, a cache of human bones was found in the 500 block of Stone Street in Flint, just north of the river. These bones were sent to an eminent anthropologist at Michigan State University, who confirmed the bones to be of pre-1800 Native American origin. More than 30 skeletons were unearthed at Stone Street. The Chippewa Tribe of Michigan was contacted and the bones were re-interred in the ground with official ceremony. As to the cause of death of the bodies, it is unknown. Is it possible that they were the massacred Sauk?

The Ephraim S. Williams battle account is indeed interesting. Although Stone Street does not sit “about a half-mile below the present City of Flint” as the account states, the site of the Native American bones found on Stone Street is approximately less than two miles away from Downtown proper. The account also states that a battle was fought about “one mile above the City of Flushing” and Mill Street, where artifacts were found, seems to be close enough. It’s interesting that Native American artifacts and remains were found at the two sites detailed in the Williams account, and at this time, no other major findings anywhere else in the County have been chronicled (as found during research of this writing).

It seems dismissive to believe that the Sauk Nation did not prosper at one time in the lands of Genesee County; just as it seems unbelievable that the Sauk would leave of their own volition. A great battle most likely occurred here more than 370 years ago. Perhaps the land is still holding the secret that will unravel the mystery.

References:

Bellin, Jacques Nicolas, and Homann Erben. Partie occidentale de la Nouvelle France ou du Canada. [Nürnberg, 1755] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/73694802/>.

Brand, N. (2008). Part of Chippewa-Sauk Indian battle waged near Flushing in 1600s. Flushing Observer. Retrieved from https://www.mlive.com/flushing/index.ssf/2008/10/american_indian.html

Chas. C. Chapman & Co. (Eds.). (1881). History of Saginaw County Michigan. Chicago, IL: Chas. C. Chapman & Co.

Everts & Abbot. (1879). History of Genesee County Michigan. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

Lawlor, J. (2008). Bones found at Stone Street development could be remains of Sauk Indians killed in battle considered by some ‘myth.’ The Flint Journal. Retrieved from https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/index.ssf/2008/12/bones_found_at_stone_street_de.html

Sauk Trail. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 17, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sauk_Trail

Wood, E. (1916). History of Genesee County, Michigan, her people, industries and institutions. Michiga Historical Commission.