“What is art to you?” I ask, not fully understanding the naiveté of my question.

“Ha!” she chuckles. “I feel like I’m back in high school. We had to write, ‘Art is, dot dot dot.’” She pauses. “That’s such a postmodern question,” she replies.

I think to myself, “How did I walk into that wall? She’s so right. ‘What is art?’ Really? What was I thinking?”

I’m speaking with Carolann Goodrich, an incredibly adept artist from Flint and sister-in-law to one of my favorite My City story subjects to date, cobbler Timothy Goodrich. I’m fumbling my way through my typical question list. When the opportunity presents itself to have audience with an accomplished professional, especially when I hold said professional’s work in high regard, it can be a little disconcerting. Trying to maintain composure, I’m not faring too well, and it doesn’t help me much to have one of my favorite local musicians, Scott Grantham of Hawk & Son, taking the seat aside us. I’m a bit distracted. I introduce the two veritable artists to each other and brace myself. I just asked Carolann a generic, interview-oriented question, and she swatted it away with ease. I have yet to get through all of my questions, and at this rate, fear asking another.

We’re meeting at Barnes & Noble, where I chose to sit in the plush chairs along the store’s wall. Carolann is incidentally just as contemplative with her response to each of my questions as was her brother-in-law Tim when I interviewed him. I suppose it’s a necessary character trait to bear in order to be a part of the family, and what a trait. If only more of us bore it, as well. Holding my breath, I await her well-thought-out response to my run-of-the-mill inquiry.

“The reason I chose realism…” she trails off and chooses to attack the question from another angle. “I don’t like that art is open to interpretation.”

I exhale. What a great response, I think. I’ve found a contemporary who is not afraid to question the blithe, egalitarian view of art that is pervasive in today’s culture. I scrap all of my questions and just listen instead.

Carolann speaks with certainty and authority, and paradoxically does it in a humble manner. She came up with sensible ambitions. Maybe her art would take her somewhere, maybe it would not; but she was willing to go wherever it took her. In high school, she would draw while in class, which helped her to retain much of what was being taught in any subject. Her friends first noticed her skill, and they would offer her lunch money-amounts of cash for minor works, but then teachers noticed; one even offered $50 for her work. Carolann the Professional Artist was birthed in that moment. She set out to hone her craft at university while pursuing religious studies, as well. This took her to a little college in Ohio, but she didn’t much fancy the structure there. She then hopped on I-75 South to Atlanta, where she studied at the Art Institute. Not long into her AI coursework, an instructor advised her to drop out; not because she couldn’t hack it, but because she was too good, and a degree would have no value unless she was definitely going into a design career. She returned to her Genesee County home with an unsure future and an undeniable talent.

Carolann speaks with certainty and authority, and paradoxically does it in a humble manner. She came up with sensible ambitions. Maybe her art would take her somewhere, maybe it would not; but she was willing to go wherever it took her. In high school, she would draw while in class, which helped her to retain much of what was being taught in any subject. Her friends first noticed her skill, and they would offer her lunch money-amounts of cash for minor works, but then teachers noticed; one even offered $50 for her work. Carolann the Professional Artist was birthed in that moment. She set out to hone her craft at university while pursuing religious studies, as well. This took her to a little college in Ohio, but she didn’t much fancy the structure there. She then hopped on I-75 South to Atlanta, where she studied at the Art Institute. Not long into her AI coursework, an instructor advised her to drop out; not because she couldn’t hack it, but because she was too good, and a degree would have no value unless she was definitely going into a design career. She returned to her Genesee County home with an unsure future and an undeniable talent.

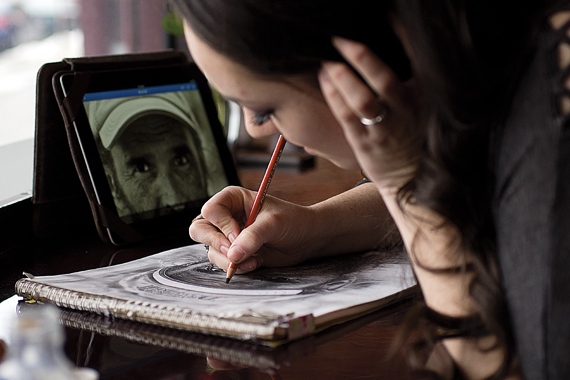

A pencil artist by preference, she primarily practices Realism. Her artwork is without limit, with subjects spanning the animate and inanimate alike, and she does each with panache and precision. Her drawing of Downtown Flint, which once decorated a wall at the Flint Crepe Co., was sold for several hundred dollars to local lawyer, Jeremy Piper. Her résumé is impressive, and her clientele, who have commissioned a dearth of portraiture, is widespread.

So, I am reclined, listening to Carolann expand on her above statement, “I don’t like that art is open to interpretation.”

“Someone might look at a picture and say, ‘It’s about the emptiness in our souls,’ and I think, ‘How do you know that? Maybe it’s not.’” In effect, in order for something to be interpreted accurately, its maker must be present in all conversations on it. Indeed, in a world where publishing and intellectual property have amassed to the degree that we are inundated with voluminous works, the general consensus is therefore now, “if you publish it, I have the right to criticize it,” and some argue that the ultimate end of the New Criticism movement is to grant completely subjective interpretation to all man. That just seems to be the nature of the beast in art and literature publication. Although I have come to terms with it, I do not completely agree with it, and I have found myself in the company of a fellow skeptic to that end. Carolann revisits her original response, about the reason why she chose realism, and ties it in with her critique of my postmodern-designed questioning and her stated dislike of universal interpretation.

“I think younger people in general just want something raw and something real. We’re sick of fake food. Look at our clothes,” she points to her boots and my boots, “they’re old-school and leather. Our music is stripped down and sounds like folk. The culture is sick of fake things.”

With that statement, it would seem that there is a little Realist in all of us, and maybe this is so. The art form of Realism gained prominence in the mid-19th century led in part by one Gustave Courbet of France. Courbet and his contemporaries did not so much reject Romanticism, which preceded Realism and pervaded Western European culture, as much as they built upon it and wedded it with other art forms, namely Impressionism. Was the combination intentional? Maybe it was and maybe it was not; but regardless of the artists’ aim, a new art form had been born, and it relied heavily on depicting natural life devoid of embellishment. Stuff just got real.

Carolann continues with her critique of Realism as life. She presents to me her most recent work, a collaborative effort with Flint photographer Chris Szumowicz, who captures images of life in Flint that Carolann translates to pencil art. Looking at the piece – a well-crafted face of a man in my town – I’m impressed. She climaxes in conversation with the declaration of her dream: to be remembered for something. “I want to have a lot of art, something that’s kind of like a legacy,” she says. She invokes the name of C.S. Lewis as an example. “When I read his work, I feel like I know him.” Although she has developed higher goals over time, she immediately acknowledges her shortcomings. She wants to produce a larger body of work, but also states “I don’t want to become so disciplined that I hate what I do.” Artists often concede that when what they do becomes the drudgery of everyday work, their creativity is stifled, but I do not suspect that Carolann’s work will ever be too stymied. She believes in herself and believes in what she does, so looming criticism and intermittent lack of discipline are not so much her adversaries.

I gather my things, take a look over Carolann’s most recent work, and we soon depart. I take with me the tested and proven true lessons of art, culture and life from one who is wise beyond her years. I also leave having tallied the Goodrich clan at being two-for-two in the category of awesomely creative family members. I would not hesitate to revisit them in the future, nor would I hesitate to promote the unique-to-Flint services of this gifted, realist and genuine lot.

PHOTOS BY SARAH REED-SZUMANSKI AND COURTESY OF CAROLANN GOODRICH